“If only I had a pound for every time a propspective new client asks me if I could ‘do CBT on them’…” said one of my therapist friends recently. I didn’t ask what they could do with the money they would amount, but from my own experiences, it is a question posed enough (in one shape or form) to make many humanistically trained therapists sigh and then ponder just what our modality is doing wrong in terms of marketing.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy “is a talking therapy that can help you manage your problems by changing the way you think and behave”, so say the NHS help pages. According to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) – an independent body set up by the government in 1999 – the evidence-base for the effectiveness of CBT makes it the treatment of choice for depression and anxiety: and indeed, the research does look convincing especially in the context of its cost-effectiveness (it can be delivered in few sessions and in a manualised way, minimalising staff input). However, CBT is not without its critics: its philosophy and its research supramacy is being called in to question.

From my experience, clients that come asking for CBT associate this method with ‘being fixed’. As a psychotherapist who is heavily informed by Buddhist ideas, this jolts me somewhat – as I don’t believe anyone is broken and needs fixing. To suffer pain in life is not an indicator that there is something wrong with us, yet some clients experience suffering as if it points to a personal failure. This might make the reader assume I am anti-CBT: I’m not, and this is the reason for writing this blog post – to explain my viewpoint and describe my experiences of using some of the ideas with clients. I will explain how I see CBT sharing common ground with Gestalt and Buddhist psychology (my two main therapeutic influences). Yet I will also draw some important distinctions. In a follow-up blog post, I will explore the commonalities and departures through the presentation of a case study (for which the situation and names are changed to protect client confidentiality).

Setting the scene: how humanistic psychotherapy and CBT see distress, its alleviation and how to go about it

I practice a type of psychotherapy called Gestalt. Like all Humanistic approaches, it is “existential-phenomenlogical”. Very simply, this means a clear examination of choice and responsibility in the situation faced, and a focus on the ‘now’ (what is unfolding between client and therapist in the room). Gestalt psychotherapy describes how people repeat (often unuseful) patterns, referred to as ‘fixed gestalts’. A gestalt therapist works to raise a client’s awareness of the pattern they are in, and how they might be setting it up to repeat (this isn’t necessarily conscious). The therapist may draw the client’s attention to how the they make ‘contact’ with life (including with the therapist), and invite the client to try things differently in co-created ‘experiments’. The Gestalt view is by increasing awareness and accepting what is happening, change automatically flows (and well-being re-instated). In other words, there is ‘no need to push the river’. Buddhist psychology has a similar view – that awareness is the only goal – and is curative in and of itself. We turn toward the distress and accept its presence in our life rather than struggle against it.

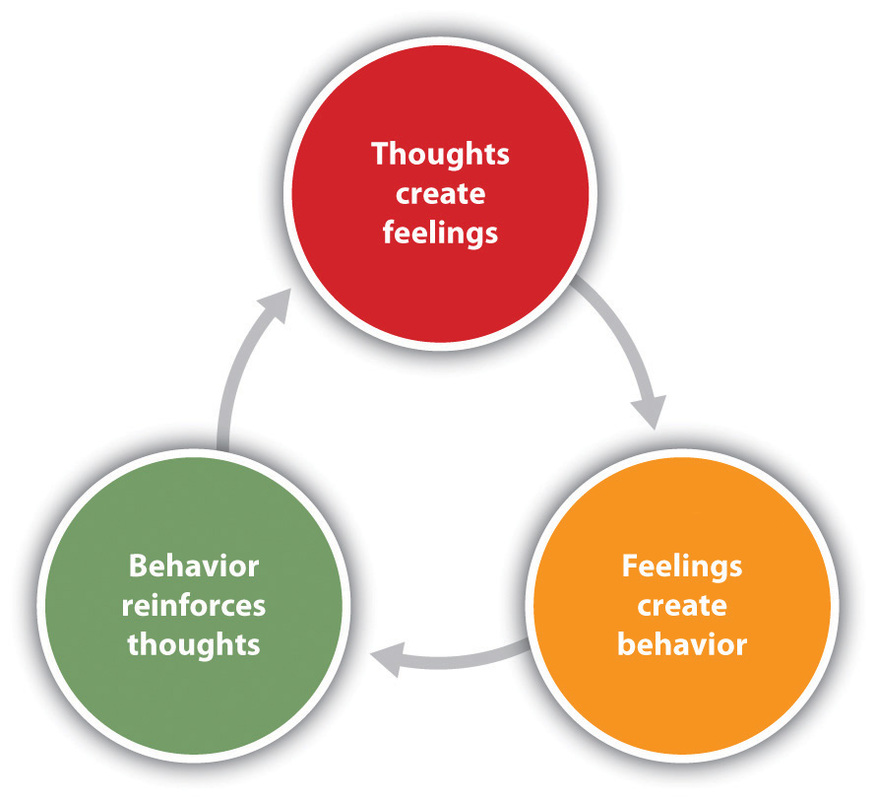

CBT believes that psychological distress is maintained by cognitive factors; and that “errors in thinking” lead to emotional distress and problematic behaviours. The therapeutic work is therefore around strategies to change ‘maladaptive cognitions’ such as case formulations and various behavioural experiments. These experiments look to the client implementing changes (to thoughts, to behaviour) and seeing the impact (on behaviour, on thoughts). CBT aims at symptom reduction and sees this as leading to an improvement in functioning and remission of the disorder. Many commentators on therapy have reported CBT as being consistent with the medical model of psychiatry with its clean ’cause and effect’ approach – which I think it part why it is so popular with those seeking fast solutions.

Common ground

Both Beck and Ellis, the forefathers of CBT, were influenced by ideas from Greek, Stoic and Buddhist thinkers. Some writers have gone as far as to describe theBuddha as the first cognitive psychologist since he explained how thoughts alter our perception, and our perception dictates our behaviour. Furthermore, we can tie together CBT, Gestalt and Buddhist ideas with the thread of ‘meta-cognition’: the awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes (in my last blog post, I talked about the work of John Welwood: he might call this ‘non-identified witnessing’). Whether called ‘helicopter thinking’, ‘awareness of awareness’, or ‘developing the watcher’, all three approaches encourage the client to consider “thoughts as simply thoughts”. Yes thoughts are real, but that does not make them true.

Awareness is therefore prized across all three systems.

- In Gestalt, Fritz Perls wrote about the “3 zones of awareness”: the inner zone of breathing, body sensations and feelings; the middle zone of thinking, beliefs and self talk; and the outer zone of the environment. He urged us to step out of the predominant middle zone, to “lose your mind and come to your senses”!

- The Buddhist psychology model of “the four foundations of mindfulness” bares a striking resemblance with its emphasis on mindfulness of the body, feelings, mental events and the ‘dharma’ (which in this use could be equated to our behaviour).

- The CBT “five-areas model” (affectionately known as the ‘hot-cross bun’**) could almost overlay the Buddhist. In any given 1) life situation, one could identify altered 2) thinking 3) behaviour 4) emotional feelings and 5) physical feelings / symptoms.

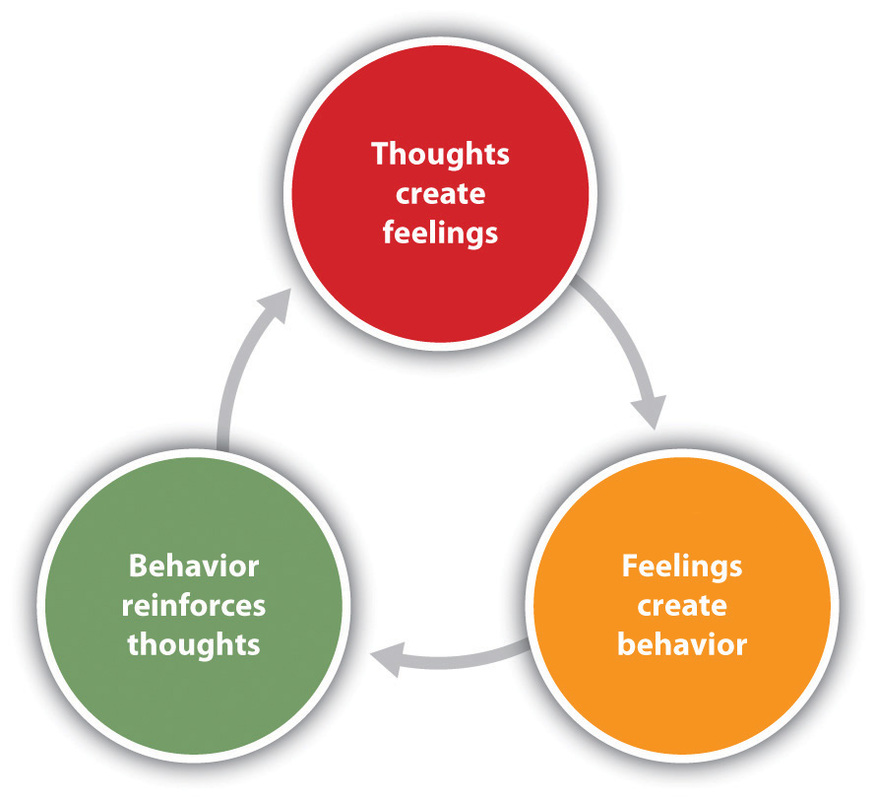

Developing awareness

Maybe its my background as a research scientist, but I love how all three of these approaches set up an experimental approach. On the meditation cushion,the meditator sits down and learns to watch their mind – very much like sitting down and observing activity in a test tube or under a microscope. In Gestalt and CBT, the therapist observes the client and listens to their predicament, gathering ‘data’ which can feed in to designing an experiment. In Gestalt, that experiment gets trialled in the room; in CBT a client might take away “home work” to try out. All 3 approaches are therefore “empirical” – ideas are tested out rather than remaining theoretical.

Acceptance rather than change

Up until now, the 3 approaches might look consistent, if not the same. However, it is what the practitioner does with the new information. Gestalt and Buddhist psychology both acknowledge the given suffering in life (in Buddhism, this is the first of The Four Noble Truths; in Gestalt, this is a nod to the existential basis of its approach – we are ‘thrown’ in to life with no choice), and from here believe we must turn toward it in order to find meaning. This is counter to what society tells us, and to be fair, what most of us want to hear!. Culturally we are losing interest in why people suffer, choosing instead to diagnose and treat. There is discomfort with discomfort and we are urged to transcend suffering. As quoted in the Oliver Burkeman piece, “CBT embodies a very specific view of painful emotions: that they’re primarily something to be eliminated, or failing that, made tolerable. A condition such as depression, then, is a bit like a cancerous tumour: sure, it might be useful to figure out where it came from – but it’s far more important to get rid of it”.

Whilst Buddhism and Gestalt use observation of the mind and experiments to increase awareness of suffering and how we contribute or perpetuate it, CBT use experiments in order to change the client’s actions and behaviours. It is in crossing this line – enforcing change rather than trusting acceptance – that I disagree: and something I will expand on in my next post. Until then, I invite you to enjoy bringing awareness to your thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and actions!

** I’ll explain more about this model next time, including the reference to the British delicacy!