I’ve recently returned from a week-long retreat with Buddhist psychologist John Welwood. I didn’t really know what to expect when I signed up for the week at Omega Institute in upstate New York. I call it a retreat, but it was equally a workshop and at times, a group therapy session with 50 + participants!

I’ve followed JW’s work for several years now, having first come across his ideas concerning “spiritual bypassing” in an article for Tricycle magazine. His primary work – looking at how to integrate the spiritual and psychological paths – has fascinated and inspired me: especially in these past 2 years whilst researching Buddhist-informed psychotherapy for my thesis. I was therefore delighted to find that JW led an annual retreat for health professionals (especially in my beloved NY, a spiritual home since completing my meditation teacher training there in 2012). I travelled armed with a copy of his 2002 magnus opus: “Toward a Psychology of Awakening” and went on to complete it for the third time. In reading it this time around I feel I gained so much more, no doubt in part because I could feel the presence of this great teacher in the written word.

As the struggle to describe a Buddhist-informed therapy within the word limits of my thesis testifies, there is much interest in bringing Buddhist meditation and psychology in to therapeutic practice right now – so I am not even going to try and attempt it in a blog post! Nor will I be able to communicate just how much my week studying and practicing with JW has impacted me, professionally or personally. I will however attempt to bring across a few salient points, starting with how JW sees spiritual and psychological work aligning. Whilst many practitioners and authors have attempted an integration, what struck me was how JW honoured each, preferring to see them as separate abeit synergistic.

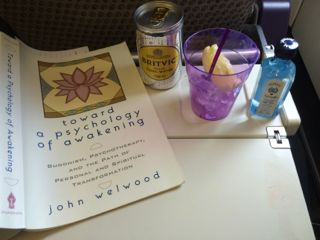

JW described psychological work like a horizontal unfolding, as achieved in Western Psychotherapy. We may go to a psychotherapist to talkthrough issues in our lives, perhaps caused by a turbulent childhood. This work helps us understand our stories, what happened and how those events and relationships continue to affect us in the present day. JW likens this to a process of “becoming”, reminiscent of Carl Rogers’ “Becoming a person”.

On the other hand, JW describes spiritual work as occurring in a more vertical sense. On the first morning of practice, I had a first hand experience of this, a sense of “dropping in” to a state of being – JW describes this as like “taking an elevator down”, and being in the flow of experience. The basic premise of his work is to help people rest in that being; to meet experience directly. What it is to be a human being, the aim of spiritual practices.

Why are the both important?

With his training in Western psychological traditions (one of his primary teachers was Eugene Gendlin, an existential psychotherapist and colleague of Carl Rogers, who founded the technique of Focusing), JW is well versed in theories of human development. He explained during the week that for most of us, our wounds are rooted in our childhood relationships. Those of you familiar with the work of British paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott will know that “good enough” parenting requires a safe holding environment, one that provides both contact and space. A lack of either of these conditions will result in a child thinking “I’m not okay”, and believing their goodness is conditional. In order to be seen and receive love, worth has to be earned. Many of us move in to adulthood still trying to prove we are okay, something JW terms “the identity project”.

The ability to let go and rest in the flow of experience is often blocked by the identity project. There is too much mistrust: there is fear that underneath our endeavours to create an “I’m okay” identity we are deficient. Any one who has tried to meditate will know how busy the mind can be – thoughts, ideas, plans, stories: the ego doing its best to solidify itself, prove itself. Buddhist psychology presents that we ARE good enough without any ego activity – what is called “basic goodness” or “primordial purity”. Our goodness is not conditional on what we do or achieve – there is nothing to prove.

Like meditation, resting in the flow of experience and simply being, is a practice. Many people will be accustomed to a meditation technique that invites a gentle attention on the breath. Resting in “unconditional presence” (as JW refers to meeting experience directly) is similar but doesn’t require being with the breath – as breath is only part of our total experience. We simply sit and rest with whatever is going on. We might notice a body sensation, a feeling, an emotion – and we resist moving in to the story.

What touched me was how motivated JW was in bringing this work to others: as a self-proclaimed “wounded healer” he has much conviction that as adults we can turn around our childhood wounding. He explained as children we were too small to digest what was happening to us: our experience was overwhelming. As adults, we aren’t that small child anymore – we have grown big enough to digest what was previously indigestible: our nervous system is now better equipped to process experience.

At this point, it is worth distinguishing the psychological and spiritual endeavours (as JW attempts in his writing on spiritual bypassing). Psychological healing is to digest what wasn’t digestible as a child. For many Western psychology traditions this goal is one of gaining a healthy sense of ego, achieving self-esteem. Freud described this outcome of psychotherapy as moving “from neurotic misery to ordinary human unhappiness”. The Buddhist aim is total liberation or enlightenment; the view (one shared by many of the Eastern wisdom traditions) is that there is no self to gain more esteem! Of course, “Helen” must exist on some level, or you would not being reading these words. What Buddhist ideas point to is that there is no inherently existing “I” that needs to defend or protect “itself”. If we sit still, we cannot look inside of ourselves and find a concrete identity – the “Helen” who is writing this is not the same “Helen” even 30 minutes ago when I started writing, let alone when aged 4-years. Spiritual work therefore goes deeper: it looks to help the practitioner realise “non-self” or “egolessness”.

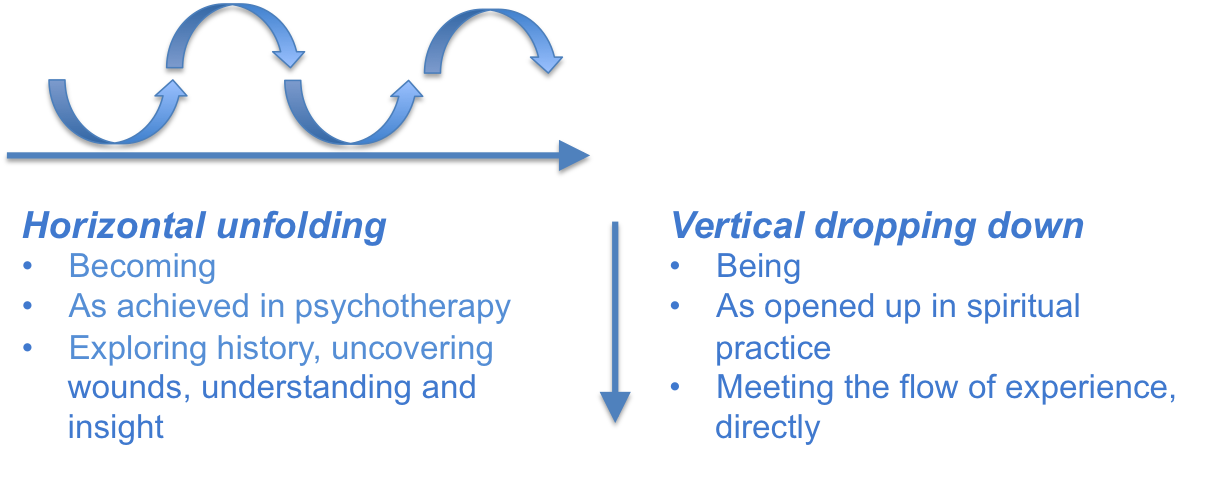

This example may help. Lets say we find ourselves in regular arguments with our partner: we find ourselves reacting and hitting out before we even know we are angry (that is, the IDENTIFICATION stage in the figure below). A first step might be opening up a gap between the appearance of anger and acting from it, long enough to realise “I am angry” (CONCEPTUAL REFLECTION). A further step might be to widen that gap a little more “There is anger” (MINDFULNESS). We can notice and label the anger, what might be called “developing the watcher”: we can learn to step back (referred to as ‘non-attachment’ in Buddhist psychology) from our thoughts and emotions, to observe them rising and falling and not acting from them. This is something western psychotherapy can achieve through dialogue, and what meditation practices like RAIN also foster.

With advances in a mindfulness practice, we can move toward UNCONDITIONAL PRESENCE, even the watcher gets dropped. There is no “anger” because there is no watcher and no-self to experience the anger. As JW explained, emotions are feelings plus a story. What can be experienced is the flow of energy – which might be experienced as pulsing or heat or tension. But, in my very act of trying to describe the sensations to you, I am setting up a distance from the flow: meeting experience directly is just being with the “is-ness”. After one morning of practicing in unconditional presence, JW asked for feedback as to how we were – I answered with this (JW considered this a poem – if it is, it is my first one!)

With advances in a mindfulness practice, we can move toward UNCONDITIONAL PRESENCE, even the watcher gets dropped. There is no “anger” because there is no watcher and no-self to experience the anger. As JW explained, emotions are feelings plus a story. What can be experienced is the flow of energy – which might be experienced as pulsing or heat or tension. But, in my very act of trying to describe the sensations to you, I am setting up a distance from the flow: meeting experience directly is just being with the “is-ness”. After one morning of practicing in unconditional presence, JW asked for feedback as to how we were – I answered with this (JW considered this a poem – if it is, it is my first one!)

I am lying in a warm bath

There is no bath

There is no water

There is no “I”

It felt as if there were no boundaries; that I couldn’t point to where I finished and the world around me started. There was such space, just expansive being. Perhaps a useful visual here is to think about Russian Dolls – the process of becoming is like separating out the different ‘selves’ we play out in life (and why); the process of being on the other hand is like being within the experience with no separation – the ‘is-ness’ of the whole dolls set.

But even the most advanced of practitioners will find this state hard to sustain (even though it can’t be sustained, because that in itself evokes there is something to try to “do”). Part of the human condition is to feel this fear of not existing (the philosophers of Europe have long pointed to such existential angst). To lose our reference points means a lack of control. Existential psychotherapists may help their clients ease this anxiety by encouraging the search for meaning in worthwhile projects; Buddhist teachings however point to there being no ground to find, and that the work is “simply” to integrate the fear. Time for my favourite Chogyam Trunpa quote: “The bad news is you’re falling through the air, nothing to hang on to, no parachute. The good news is there’s no ground.”

How do we “drop down”?

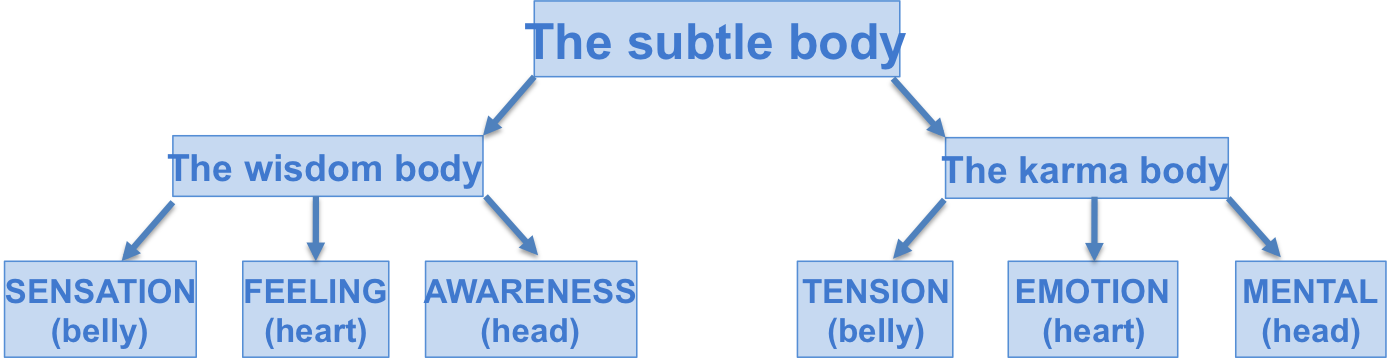

JW introduced us to a range of practices in the programme: some to music, some lying down, some moving, some dialogue in pairs – but all helping us tune in to our “subtle body” (the level at which we can meet the flow of our experience directly). He has developed a practice to help his clients experience unconditional presence: presented here in five steps, but by no means always this linear:

1. Turning toward the feeling

2. Noticing how it feels to acknowledge the feeling

3. Allowing the experience, giving it the space to be

4. Opening to feeling it, opening the heart

5. Entering in to it, stepping in the feeling (non-separation)

You may notice how much it has in common with the practice of RAIN: recognise, allow, investigate, and nurture. There is also much in common with the Western therapeutic practice of Focusing, where clients are encouraged to explore a “felt sense” of an issue or dilemma. However, whilst focusing helps people make meaning of their feelings, the key to this unconditional presence is dropping any narrative associated with feelings that come up. The other essential ingredient is boredom: if we can sit with our feelings for long enough, we can “bore the ego to death”!

Watching him go through this process with people (and indeed, getting the chance to work with him 1-2-1 in the presence of the group) enabled me to witness the transformational power of this approach. Furthermore, to watch a practitioner who combines expertise and wisdom with grace, love and presence was awe-inspiring.

Obstacles as the path

It isn’t always plain sailing in this practice – as well as navigating the boredom, another obstacle can be a sense of not feeling anything. I speak from personal experience, someone who has historically prioritised intellect and thinking, and holds that “my heart is playing catch up” and that “I don’t do feelings as well as I think”. Working 1-2-1 with John, he pointed out the story I was telling myself and asked me to stay with what I was describing , that being “the feeling of no feeling”. It felt like eternity (and time always goes slower when you know there are 50 others in the room – I wondered whether their boredom would be enough to disintegrate my ego!). Using presence requires a dash of patience and a dash of compassion. Interesting etymological note: The word patient originally meant ‘one who suffers’; whilst compassion is to ‘suffer with’. I know when working with my clients how hard they find it to open up and accept the position they find themselves in and to see their childhood strategies (developed to help them survive) in a kinder light – they want rid, yesterday. To experience pain and see how we have historically coped with it can feel like we have failed somehow. But without first feeling that pain, we cannot bring compassion. As I sat with my numbness, I suddenly felt a strange mix of sadness and pride for that little girl who learned (so well) to think rather than feel.

Joining Heaven and Earth As the week progressed, I experienced more and more space in my being. As I sat one morning (on “my bench” besides the Omega garden), I reflected upon how ordinarily it is only when in nature that I touch my greatest moments of contentment and expansiveness. JW explains in his writing that experiencing “one-ness” is a lot more common in the great outdoors: as if there is something awesome and sacred that can be contacted. Yet what this week taught me was that same “one-ness” can be experienced by going inward: the inner space is just scarier to contact (because it points to our egolessness). By sitting on our cushions we can connect matter and spirit, practicality and vision, ground and space, form and emptiness.

As the week progressed, I experienced more and more space in my being. As I sat one morning (on “my bench” besides the Omega garden), I reflected upon how ordinarily it is only when in nature that I touch my greatest moments of contentment and expansiveness. JW explains in his writing that experiencing “one-ness” is a lot more common in the great outdoors: as if there is something awesome and sacred that can be contacted. Yet what this week taught me was that same “one-ness” can be experienced by going inward: the inner space is just scarier to contact (because it points to our egolessness). By sitting on our cushions we can connect matter and spirit, practicality and vision, ground and space, form and emptiness.

Since returning home and getting back in to work – seeing clients, starting a new job – I have noticed how the mind is attempting to contract and how “I” is tempted to start defending itself. Yet, there is a depth to my awareness that was previously untapped and I am more able to pull myself out of that contracting and shutting down.

On the first day of the retreat JW took us through a practice and – as was to become the norm – he asked us for some feedback. I took the microphone and offered “wow, what if I could sit with my clients and offer them the same level of presence I’m feeling now?” I believe I’ve found the way.