Teaching over, marking completed, exam boards seen to…a chance now to reflect on curriculum development. I have been teaching on these courses for six years; and every now and then it is good to return to the curriculum and taught content and update the material to include the latest in theoretical and philosophical thinking. I know I would say this, but I believe attending an academic institution to undertake training to become a therapist really stands our trainees in good stead. There is much overlap in the skills needed to be a good therapist with those in academic study: for example, the ability for critical thinking. I also reap the benefits of this – I am in no doubt that being an educator of therapists keeps me on my toes so to speak in ensuring my practice remains fresh and informed. I enjoy the blend my two vocations bring, and my book is very much fuelled by this. And so, this past week I have been thinking about one module I teach in particular – one that focuses on the nature of change in psychotherapy.

I teach on two programmes at the University: the post-graduate diploma in Humanistic Counselling and Psychotherapy, and the Masters in Psychotherapy. Students can train to become counsellors by completing the two year PGDip programme; and some decide to stay on for another 2 years to complete the MSc. The latter allows a practitioner to register as a psychotherapist. I am often asked what the difference is between counselling and psychotherapy: by potential clients, but also students who are thinking about staying on to do the MSc with us. You’ll find a brief answer to this on my FAQ page, and here I’d like to elaborate on one critical difference – the nature or the ‘order of change’:

First order change deals with the existing structure, doing more or less of something, and involving a restoration of balance.

Second order change is creating a new way of seeing things completely, we might say a re-structuring of the system.

Counselling has the aim of first order change. Typically clients come looking for help with a ‘problem’, and the counsellor helps in some kind of restoration of stability. Bereavement counselling is an example.

Psychotherapy on the other hand offers the client an opportunity to deconstruct the self who is experiencing the problem. Rather than stability, the end result is often a new relationship to the instability.

“Why on earth would I pick psychotherapy?” I hear you cry! Well, because as life progresses, we come to realise there is problem after problem. And, as the Buddhist monk Shantideva said:

“Where would I find enough leather

To cover the entire surface of the earth?

But with leather soles beneath my feet,

It’s as if the whole world has been covered.”

By working on self, or working with our mind, we cut to the root.

The writing of my book – one that looks at the integration of the Buddhist dharma into psychotherapy work – has had me deeply consider what second order change is within the Humanistic therapeutic approach. As an aside, this is one aspect of that critical thinking I mention above – using one approach as a lens to critique another. The Buddhadharma, in my view, brings a powerful method through which direct experiencing can be fostered. And why is this important or indeed relevant to the Humanistic practitioner?

“Change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not.” – Arnold Beisser

The paradoxical theory of change is a central construct within Gestalt psychotherapy. What it conveys is that switch in relationship to our distress I mentioned earlier as a constituent of second order change. By increasing our awareness of ALL that we are, our relationship to it shifts. And awareness isn’t just insight; it is fully experiencing the different aspects of our self. Allowing, dare I say even embracing.

A classic example of this from my private practice work is what we might call the client who lives under ‘the tyranny of the shoulds’, a persistent and often loud internal critic who is always having an opinion and causing the client to believe “I should” or “I should not”. These introjects are messages we take on in childhood and continue to block us from fully living. The aim of psychotherapy is not to ‘get rid’ of this voice, but rather to open to it, come into relationship with it, and know what it needs. The ‘top dog’ needs as much empathy as the ‘under dog’ – although its mode is rather heavy handed, that ‘shoulding’ voice is only trying to protect us.

Insight is not the same as experiencing, it is worth repeating. We have to feel the affect of both the top dog and the under dog within us (and why Gestalt work often includes two chairs – so they client can put these two parts in dialogue and feel each part, fully).

What does it feel like to be the persecutor? Where do they reside in experience? What are the physical sensations, the felt-sense and feeling tone?

Likewise, what is it like to be on the receiving end? The physical, feeling, emotional impact?

What I have come to appreciate with Buddhism is the complete system of psychology and practice, take the four foundation of mindfulness for example. Buddhism doesn’t have the monopoly on developing bodily awareness. Indeed, both Focusing and Gestalt which lie in the broad church of the Humanistic paradigm) can be equally powerful. I say ‘can be’, because like most things, the capacity of the practice relies on the practitioner. Part of my current reflection on curriculum is how we can not only put across the theoretical constructs of the paradigm, but also how to bring it to life in the room with a client. Without this ‘praxis’ the theory remains just that, and we can end up being ‘top heavy’ and conceptual.

One concept in the Humanistic therapeutic approach is that of ‘actualisation’. For Humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow, self-actualisation was the pinnacle of his hierarchy of needs model. Carl Rogers however saw this not as a state, but an actualising tendency present in all living things. This is at the root of the humanistic therapeutic view on human nature: we all want to express ourselves creatively and reach our full potential.

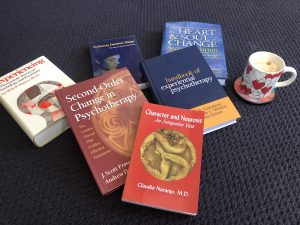

When I discuss the nature of change with our new MSc student cohort this autumn, I want them to be able to formulate how actualisation relates to second order of change; to be able to articulate not only what it looks like in a person (themselves for a start), but also what interventions we, the therapists, use in the room to foster it. The reason this feels important is having looked at the work of Alvin Mahrer and the mighty tome “Experiencing”. Nearly 900 pages long, it has taken me the Pandemic years to only now have come close to finishing it! Toward the closing chapters Mahrer discusses the nature of change or ‘optimal states’. For him, it is not just actualisation; there is a necessitated precedent of integration. In fact, the move toward the optimal state is described in a four-step sequence:

- being in a moment of strong, full feeling and accessing or opening up an inner, deeper experiencing;

- appreciating and welcoming this inner, deeper experiencing;

- undergoing a radical, transformative shift into being this inner, deeper experiencing in the context of earlier life scenes;

- and being and behaving as this integrated, actualised new person in this new person’s extra therapy world.

Not only is there a precedent to actualisation, Mahrer emphasises there is work to do in actualisation, it is not the automatic and organic one that Rogers’ conveys. I won’t go into much more detail here other than to say, Mahrer also adds that change relies upon another process – symbolisation: we feel and integrate our deeper experience but we also need to make meaning of it (cue the power of Focusing, and establishing the felt-sense of situation). Bringing this all back to first and second order change is important; and it might explain something of a cultural aspect around the Rogerian or Person-Centred Approach (often seen as a model of counselling); and the other modalities within the Humanistic fold like Gestalt, Focusing and what are often now referred to as the ‘experiential psychotherapies’. Rogers emphasised client’s empathy toward their deeper, inauthentic parts; Mahrer sees the deeper potentials as needing full experiencing, embracing, and harnessing to make meaning of their role in our loves.

Not only is there a precedent to actualisation, Mahrer emphasises there is work to do in actualisation, it is not the automatic and organic one that Rogers’ conveys. I won’t go into much more detail here other than to say, Mahrer also adds that change relies upon another process – symbolisation: we feel and integrate our deeper experience but we also need to make meaning of it (cue the power of Focusing, and establishing the felt-sense of situation). Bringing this all back to first and second order change is important; and it might explain something of a cultural aspect around the Rogerian or Person-Centred Approach (often seen as a model of counselling); and the other modalities within the Humanistic fold like Gestalt, Focusing and what are often now referred to as the ‘experiential psychotherapies’. Rogers emphasised client’s empathy toward their deeper, inauthentic parts; Mahrer sees the deeper potentials as needing full experiencing, embracing, and harnessing to make meaning of their role in our loves.

All this to say, there is an invitation to Humanistic practitioners to really know not just the concepts but HOW this plays out in the journey toward wholeness, or what Jung would call ‘Self’ (the process of individuation, which probably equates to Mahrer’s due of integration and actualisation). We become intimate with our shadow NOT to get rid of it, but instead to illuminate it and become wiser through it.