A friend and I were recently talking about our experiences of living through this pandemic, and how it increases the “driving pressure” on what are already challenging situations: I was talking about the nature of my work and the intensity of Ngöndro; she is currently going through the sale of her mother’s house and deciding where to live. We’ve probably all experienced times in our life when there is a sense of “too much to do” and every day can feel like a victory to even get through…to then have to do it again the next day, and the next.

A friend and I were recently talking about our experiences of living through this pandemic, and how it increases the “driving pressure” on what are already challenging situations: I was talking about the nature of my work and the intensity of Ngöndro; she is currently going through the sale of her mother’s house and deciding where to live. We’ve probably all experienced times in our life when there is a sense of “too much to do” and every day can feel like a victory to even get through…to then have to do it again the next day, and the next.

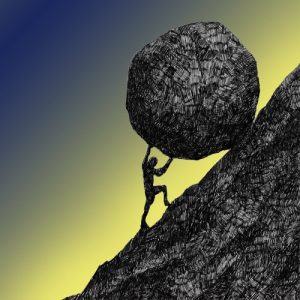

My friend and I had recently read Charlotte Joko Beck’s book “Nothing Special” for our book group. In this collection of Zen teachings, Joko Beck titles one chapter “Sisyphus and the burden of life”. Those of you who know this Greek myth will know that as punishment, Sisyphus was to push a huge rock up a hill every day for it to only fall to the bottom again…for eternity. The existential philosophy movement often use this myth to talk of the ‘absurd’: the fundamental conflict between what we want from the universe and what we actually find in it; to want meaning and order, to only be greeted by formless chaos. This cannot be reconciled, and instead we are urged – by Albert Camus in his book on the myth – to face this contradiction and maintain constant awareness of it. In Sisyphus’ case, he must perpetually struggle with his task without hope of success and accept life is no more than this – and he can then find happiness in it.

It can sound somewhat bleak, but “being with things as they are” has helped me manage my reaction to this pandemic. I continue to find myself oscillating between resignation and hope but I feel less thrown by the enormity of it all. At the beginning, I held out for the end, felt I was treading water until I could resume again. Nearly a year later, I am better adjusted and have less sense of this being a “waste” of life; instead continuing to live with the struggle as part of that life. Unlike our poor Sisyphus, there WILL be a day when we no longer have to push the rock of pandemic uphill – but there will be another rock. This is the nature of life. As the Buddha described in the first of the Four Noble Truths “There is suffering”.

As my friend and I recollected Joko Beck’s take on Sisyphus, we talked about how our narrative of experience is the cause of this suffering. If we wake up with the perspective of “here we go again”, we add weight to our rock. The task becomes a burden, or as the Buddha described, pain becomes suffering. Likewise, if we also project “and I’ll be doing the same again tomorrow”, the hill might feel steeper today. Suffering comes from bringing in a commentary – from the past which has gone, from the future which is yet to be: this commentary adds weight to our present. Even the optimistic or hopeful “it will be over one day” is a rejection of the moment now. Memories of the past and predictions of the future arising in the present are what fuels the cycle of suffering (referred to as samsara in the Buddhist teachings).

How DO we find contentment in this life then? Surely there is more to it than accepting this bleak outlook? Joko Beck:

“Because we are human, we think that feeling good is the aim of life. But if we simply push our current bounder and practice being aware of what goes on with us as we push, we slowly transform”.

What is the nature of that transformation? Another chapter in Joko Beck’s book describes the difference between experiences and experiencing, one that I will try and illustrate using our protagonist. Sisyphus has the experience of pushing the rock up the hill each and everyday. Sisyphus (subject) pushes the rock (object). Joko Beck emphasises this subject-object duality, me and that. As soon as we make our world one of objects “out there”, there is a separation in space: me (here) and that (there). Furthermore, Sisyphus will go to bed each night thinking about the rock that was and the rock that will be. Our memories and our predictions across time take over. The world of time and space arises and life becomes a series of experiences “and we divide the world up into things to avoid and things to pursue” Joko Beck points out.

Experiencing on the other hand is outside of space and time. What if Sisyphus closed his eyes as he pushed the rock – so he cannot see the rock nor the top of the hill? What if he just felt the surface of the rock, its texture, its shape? What if he just sensed the tension created in his arms as he pushes, in his legs as he walks? When talking about this with my friend the other day, we both closed our eyes and I repeated a teaching point from Rupert Spira “right now, how do you know you have a body?”. If we just allow experiencing (as it arises), what sensations do we feel? What do we directly perceive? It is tempting to say things like “I feel a tingling in my hands”. What if we removed the “I” and the “hands”, the self-object split and just rested with “tingling”? Experiencing is the verb of our life. It is outside of both space (no subject, no object) and time (its not including memories of the past, predictions of the future). Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche refers to this as “the fourth moment” because it isn’t even happening in the present – experiencing is too short and too soon gone to pin down to time.

As I am writing this, I pause and look up. I engage that position of “experiencing”. For me, it occurs when I move attention to my back body and rest in awareness rather than attention on what I am doing. Try it: as you read this, move your attention from what you are reading to that that knows you are reading. You might pick up that non-separation, negation of space and time. It does take practice…

…and I have been working with this in my own practice: primarily in my everyday life, but also in my Ngöndro. I have made no secret of how challenging I have found Ngöndro practice this past 18 months. But slowly, applying “experiencing” to my prostrations and visualisation is bringing about a shift. I am identifying less with the rumination (resistance, dread, anxiety) and more with the awareness that is experiencing body movement, activity of mind or whatever is arising. I’m nearing the end of this phase of Ngondro; so it is timely that there is a surrendering to “what is” just when the “is” is about to change! Who knows, maybe there is a risk of lamenting for “what was”.

Of course, none of this is ‘wrong’; and the thoughts, rumination, nostalgia, regret, dread etc are just part of the package of “experiencing”. A I often teach mediation students or clients, there is nothing wrong with thinking. The aim is not to stop thinking but rather to notice our identification with the thoughts, the beliefs, the stories and instead bring attention to what is actually happening in the moment.

I wonder if Sisyphus, still in his eternity of pushing, has worked this out yet?