In my last blog post, I talked about some of the theory that underpin CBT, Gestalt, and Buddhist ideas in relation to therapeutic work. As a practitioner who works mainly in relational psychotherapy (under which we would include Gestalt and Buddhist ideas), I have been intrigued by the ascendence of CBT in our national health system in the UK. I believe it wise to become familiar with a practice before making a sound judgement on its use: and indeed, this is how I feel with CBT. Whether relational psychotherapists like it or not, CBT remains the “treatment of choice”, and many clients (new ones, old ones) will have dealings with it, and will form judgements on our work with them based upon those experiences. We also need to know CBT well enough to understand what makes it different to our own approach so we can then explain this to our clients*. Completing some training in CBT was therefore important to me, allowing me to use some of the ideas in my work, and to help me appreciate truly how it resonates (or not) with my own practice.

In my last blog post, I talked about some of the theory that underpin CBT, Gestalt, and Buddhist ideas in relation to therapeutic work. As a practitioner who works mainly in relational psychotherapy (under which we would include Gestalt and Buddhist ideas), I have been intrigued by the ascendence of CBT in our national health system in the UK. I believe it wise to become familiar with a practice before making a sound judgement on its use: and indeed, this is how I feel with CBT. Whether relational psychotherapists like it or not, CBT remains the “treatment of choice”, and many clients (new ones, old ones) will have dealings with it, and will form judgements on our work with them based upon those experiences. We also need to know CBT well enough to understand what makes it different to our own approach so we can then explain this to our clients*. Completing some training in CBT was therefore important to me, allowing me to use some of the ideas in my work, and to help me appreciate truly how it resonates (or not) with my own practice.

I want to share a case study with you this week, one that helps demonstrate where CBT works very well, and where I believe psychotherapy based on the relationship is deeper and longer lasting. Let me introduce you to “Sophie” (the situation and names are changed to protect client confidentiality); a 21 year old Italian language student visiting the UK for a year as part of her degree course. Sophie was experiencing “a lot of anxiety” and found herself “constantly thinking”. She had found my website having searched for mindfulness classes, as she had head that “meditation will help me stop thinking”. As Sophie explained more about her health in our first meeting, she told me that she was “fed up with not knowing what is wrong with me”, as alongside her anxiety she also presented with bad skin problems, disturbed sleep, teeth grinding and “to top it all”, irritable bowel syndrome. I received Sophie’s message: I was her last hope – she was thinking of quitting her studies because this was all feeling too much for her.

At first, I was reluctant to bring forward ideas from CBT: I was concerned that bringing “techniques and tools” in to our relationship would give Sophie the idea that she was broken and needed fixing. However, when she revealed she only had 8 weeks left in the UK and we were setting up a short term arrangement I weighed up the pros and cons. One thing I DO appreciate with the CBT approach is the psycho-education and “homework”: Sophie was bright and dynamic, I trusted that she would pick up some useful learning which she could come back to once she returned home to Italy.

Another factor in using CBT with Sophie was knowing how much published research existed supporting CBT in cases of anxiety:

- Anxiety affects 3/10 people in their lifetime (Kessler et al 2005)

- High support for CBT with anxiety disorders in adults (Hoffman et al 2012)

- Superior over psychopharmacology (Fedoroff and Taylor 2001)

- Shows preliminary efficacy with physical symptoms (Altayar et al 2015)

Research by Drossman (1999) prompts practitioners to consider a more bio-psycho-social model of anxiety; that much of the impact of CBT is in fact a ‘placebo effect‘ (upto 80%). Just being ‘in therapy’ can bring on better health, no matter what the therapy is. In other words, the therapist-client relationship is critical, even in manualised treatments such as CBT. Whilst I was going to be using CBT ideas with Sophie, I was not letting it take centre stage – it would be delivered within a relational field, just a way to bring us alongside rather than something I would be doing to her.

In the first couple of sessions, Sophie explained her current life and her early experiences. She told me she had had a “generally happy childhood” up until the point she went to a new school (at age 9): at which point she experienced bullying and a lonely time. She threw herself in to her school work to compensate, and this won her praise from her very critical Father. She described her Mother as “really supportive” and how they were “very close” – even more so now that she was separated and divorcing her Father. This exploration was completing the first task in CBT work: the case formulation. It is considered the foundation of the approach and starts the client and therapist formulate a picture of the predicament and the possible triggers. Various versions exist, but key components include:

- Ascertaining the issues and the goals

- Key core beliefs and generalising statements about the self and the world

- Unhelpful assumptions such as life rules: the shoulds and the musts

- Vicious cycles and things that keep the problem going: are there safety behaviours or compensatory strategies?

- Triggers that set the problem off now

- Modifiers or things that make it better or worse

- Factors contributing to vulnerability: maybe childhood experiences or genetic factors

- Critical Incidents: looking at what started the big problem, including recently

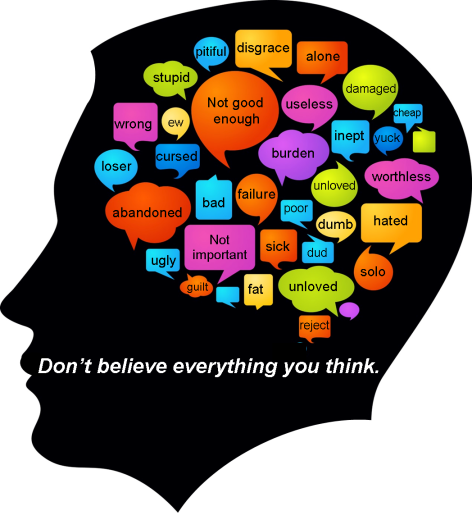

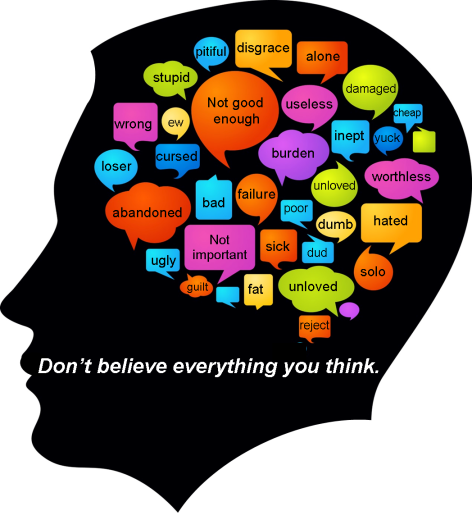

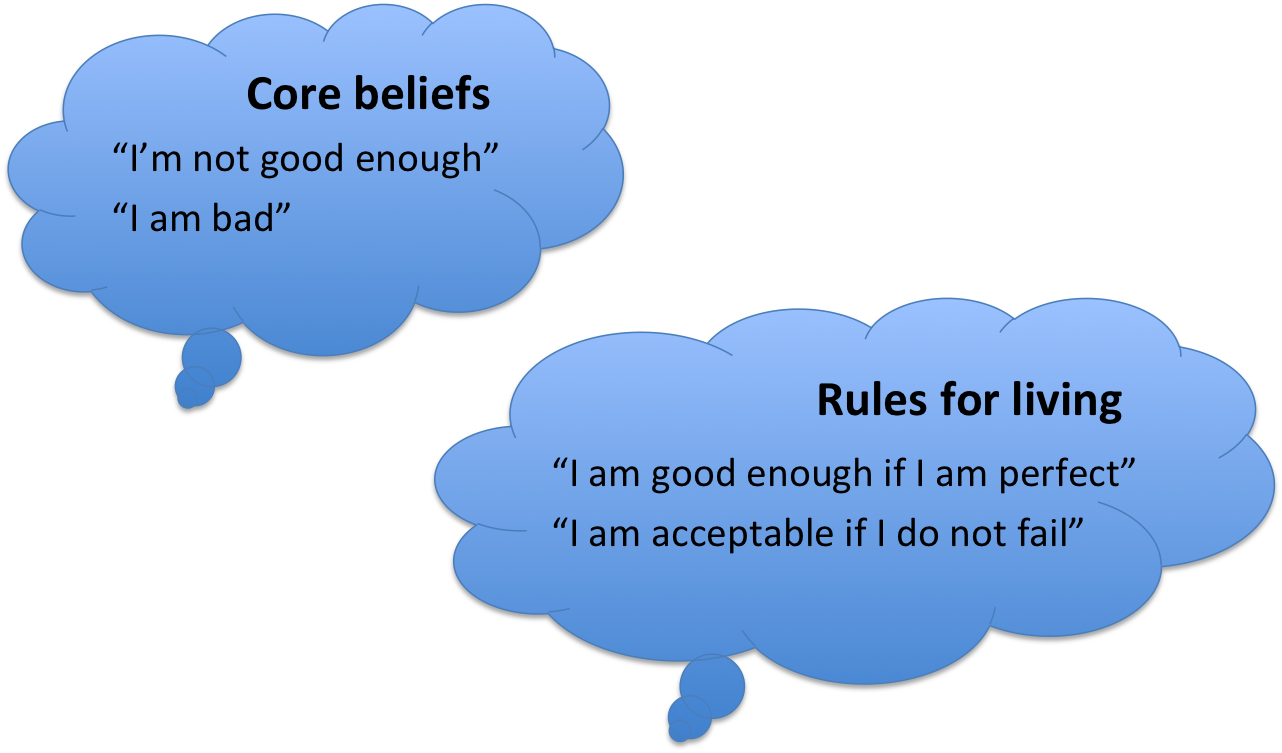

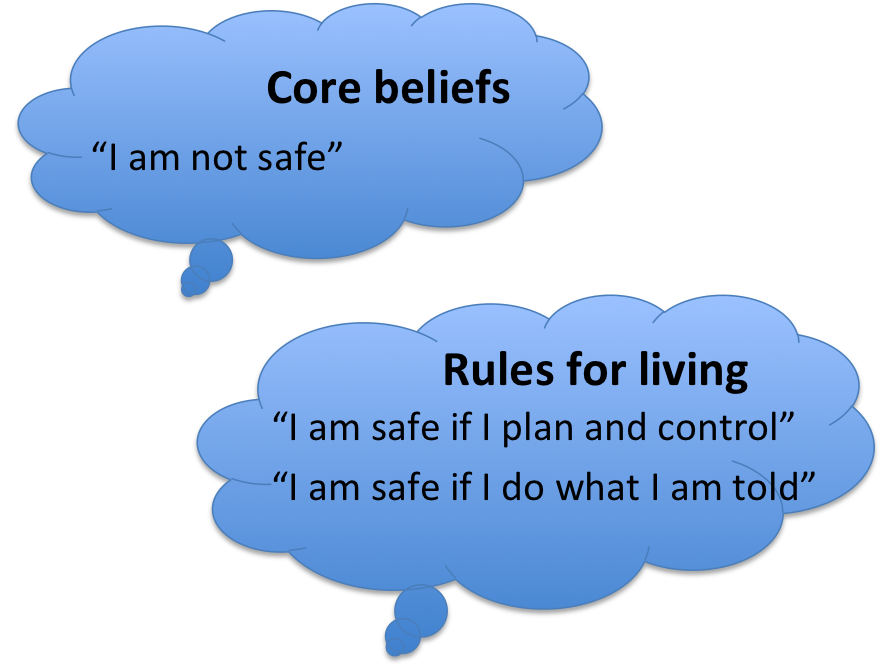

We were easily able to identify Sophie’s core beliefs and rules for living. Within two sessions, Sophie was gaining valuable insight – she came back the following week giving me examples of what she was now seeing and how she was understanding her predicament like never before. Sophie explained something that had occured that week: when on the phone to her Father, he started to criticise her for not having got in touch with her cousin for her birthday. It had led to a particularly bad night’s sleep and caused her IBS to play up. I asked if she would like to try something: I showed her a blank form which in the CBT world is known as the Five-area model, or more affectionately, “the Hot-cross bun”.

I moved my chair alongside Sophie and gave her the pen. We put the sheet in front of us and we worked through the form, filling in the boxes during our conversation. We noted together how easily she could recall her thoughts, her emotions and her behvaiours in that moment; but what was more difficult was accessing her bodily sensations. She could not recount to me the physical symptoms of her anxiety as she felt them in the moment. Even in our discussion, Sophie articulated how reluctant she felt in turning inward – something she explained through her experience of IBS – “why would I? I feel anxious all the time and I just want to get rid of this”. She found it hard to understand why turning toward these symptoms was going to be helpful, it risked being overwhelmed.

I moved my chair alongside Sophie and gave her the pen. We put the sheet in front of us and we worked through the form, filling in the boxes during our conversation. We noted together how easily she could recall her thoughts, her emotions and her behvaiours in that moment; but what was more difficult was accessing her bodily sensations. She could not recount to me the physical symptoms of her anxiety as she felt them in the moment. Even in our discussion, Sophie articulated how reluctant she felt in turning inward – something she explained through her experience of IBS – “why would I? I feel anxious all the time and I just want to get rid of this”. She found it hard to understand why turning toward these symptoms was going to be helpful, it risked being overwhelmed.

I completely understood Sophie’s reaction – I was encouraging her to turn toward the very experience she had been fighting to avoid. I knew my first task was to help normalise some of what Sophie was experiencing. The first step was bringing understanding and admiration to her “shutting down” an awareness of her physical life. At the time of an initial trauma or wounding, we humans find all sorts of inventive ways to avoid suffering and pain (from mild ‘deflections’ to more severe dissociation). A second step was to explain the physiology of fear. One of the things I appreciate about CBT is how its focus on psychoeducation (and many people who have received CBT will remember the various handouts and worksheets that accompany the process). I described the “fight or fight” response to Sophie; how we are hard-wired to become anxious in the face of threat – so rather than her physiology “failing” her, it was in fact helping her detect a lack of safety. All we had to do was to work out how to re-calibrate it: the anxiety response was jacked up a little from a childhood situation which felt overwhelming, but was probably more digestible as an adult. The main aim here was to decrease her anxiety about her anxiety**. The more Sophie learnt to tolerate the bodily affect, the more she began to see the symptoms of her anxiety as a useful indicator of “what’s going on here, something isn’t right?”.

As a Humanistic psychotherapist who practices Gestalt psychotherapy, consideration of the ‘here and now’ experience isimportant. We could call CBT a ‘there and then’ therapy – as seen when Sophie brought in the experiences with her Father: it was outside of the therapy room, some time in the past. Helping clients tune in to their experience in the ‘here and now’ is one way that Humanistic therapy sees healing taking place. Therefore, our next task was to help Sophie work with her experience as it was happening. One example of this was planned – Sophie and I set up a common Gestalt ‘experiment’: Chair work. We set-up two chairs, Sophie taking it in turns to sit in each one as she played the part of her Father, and then herself in relation to her Father. As she dialogued with ‘her Father’, I asked Sophie questions that helped her practice tuning in to her experience as it is: this really helped identify what CBT calls “negative automatic thoughts” as well as helping her identify where those thoughts live in the body. We also used the Chair work to play with language and notice its impact on thinking and feeling. In Gestalt, we do these experiments to heighten awareness NOT to enforce or suggest changes.

I’d like to mention an additional situation that became pivotal in the work with Sophie – when I became the “activating event”. With a growing awareness of her inner world, Sophie was able to articulate feeling sick when she arrived at our 5th session; which as we discussed and explored it, transpired as a common experience when she was in the company of others. We completed the “hot cross bun” in real time, focusing on the how of experience rather than the why. When we got to the testing ground of the physical, I invited Sophie to try “Focusing”, a technique developed by Eugene Gendlin, that helps identify the “felt sense” of a situation (the meaning we might ascribe to experiences in our body). We began to put together the final pieces of the puzzle: for Sophie the presence of others introduced expectations, and a need to live up to those expectations. We were able to look at the rules for living (see the figure on the left) in the context of her typical behaviour when she was triggered. We noticed how she would often contact her Mother when experiencing high anxiety. But what was interesting was bringing in the context of her being so far away from her Mother now – “My Mother cannot protect me”. Chair work helped us uncover an ambivalence: a part of her wanting to stay safe (protection afforded by her Mother), whilst a part of her wanted her freedom (a desire to separate from her Mother). We discussed anxiety as an energy, perhaps one brought up in the tension between these two opposing parts.

I’d like to mention an additional situation that became pivotal in the work with Sophie – when I became the “activating event”. With a growing awareness of her inner world, Sophie was able to articulate feeling sick when she arrived at our 5th session; which as we discussed and explored it, transpired as a common experience when she was in the company of others. We completed the “hot cross bun” in real time, focusing on the how of experience rather than the why. When we got to the testing ground of the physical, I invited Sophie to try “Focusing”, a technique developed by Eugene Gendlin, that helps identify the “felt sense” of a situation (the meaning we might ascribe to experiences in our body). We began to put together the final pieces of the puzzle: for Sophie the presence of others introduced expectations, and a need to live up to those expectations. We were able to look at the rules for living (see the figure on the left) in the context of her typical behaviour when she was triggered. We noticed how she would often contact her Mother when experiencing high anxiety. But what was interesting was bringing in the context of her being so far away from her Mother now – “My Mother cannot protect me”. Chair work helped us uncover an ambivalence: a part of her wanting to stay safe (protection afforded by her Mother), whilst a part of her wanted her freedom (a desire to separate from her Mother). We discussed anxiety as an energy, perhaps one brought up in the tension between these two opposing parts.

This is an example of how exploration of the ‘here and now’ (the felt experience Sophie had of being in contact with me) can unlock the ‘there and then’ roots in formative relationships (the wish to be protected yet free of her Mother).

Hopefully the reader will appreciate there was a lot more nuance in the relationship with Sophie than can be described here. However, I hope these two blog posts have provided some food for thought for those therapists wishing to visit CBT in their relational therapy practice; and for those clients who have an interest in CBT and want to understand how it came be used to (in my opinion) greater and longer lasting effect. I’d like to leave you with a summary of the pros and cons, in my experience, of using CBT:

On the positive side of an integration in to relational psychotherapy:

- CBT is helpful in helping clients notice their thinking and the resulting behaviour patterns: this was critical in my work with Sophie

- Filling in worksheets together aided the “moving alongside” that all Humanistic therapists privilege: sharing a task helped build the relationship in a non-threatening way, and arguably increased the rate Sophie and I developed our working alliance (important in such short term work).

- Inviting inter-sessional work also helped Sophie keep momentum; and it aided in what all Gestalt and Buddhist orientated therapist prize – increased awareness.

On the negative side:

- CBT and relational psychotherapies do not share the same view of what causes and what alleviates psychological and emotional distress. For the therapist, this means keeping an eye on what is best for the client – I could have followed a more ‘pure’ CBT approach with Sophie, but I deviated from strict development of ideas because I prioritised what Sophie was bringing each week i.e. CBT work ordinarily builds on the content of the week before; Gestalt relies on what is ‘figural’ in each session

- Bringing ideas from an approach like CBT can set the therapist as ‘the expert’. Of course, clients come to therapy to get help; but with time they begin to understand that a therapist is not there to give advice or the answers. If in the beginning of our work I had taken up the role of expert, Sophie would not have taken control of her process and become independent. For me to have told her what to do would have in fact perpetuated what Sophie already knew: protection yet suffocation. Relational psychotherapy approaches helped me identify how I was feeling in relationship with Sophie (the maternal counter-transference) and side-step the invitation to play the part in Sophie’s life that was not helpful.

Concluding, CBT can help the Gestalt psychotherapist (and other relational modes of therapy) in that it provides useful ways to help raise a client’s awareness. However, to follow its methods through to changing a client’s thinking and behaviour is to deny the client’s autonomy, choice and responsibility: what Gestalt and other existential approaches deem central to long lasting change. This is my experience of CBT, and I would love to hear the experiences of others – whether a client or a therapist. Do get in touch.

——-

*It is for these reasons that we include training in CBT on our MSc Psychotherapy training at the University of Brighton.

**Buddhism has a useful understanding of how we coat a layer of suffering on top of the pain: a teaching on the “two arrows” – the first arrow is the felt experience; the second arrow is stories we tell ourselves, the resistance to the first arrow.