I spent last week luxuriating in writing time. I finished a first draft of my book in the autumn months, and following a period of incubation, I returned to the manuscript with the intention to “know and grow” it more fully. I enjoyed reconnecting with the text. Equally, there was also a sense of relief that – on the whole – I still standby the content and shape of the 10 chapters.

I spent last week luxuriating in writing time. I finished a first draft of my book in the autumn months, and following a period of incubation, I returned to the manuscript with the intention to “know and grow” it more fully. I enjoyed reconnecting with the text. Equally, there was also a sense of relief that – on the whole – I still standby the content and shape of the 10 chapters.

There is one writing task remaining – what most books enact through an afterword or an epilogue. Given this is my first book, I needed to do some research to understand which of those approaches is more suitable for a non-fiction text. The journey this book has taken me on and this being a very personal take on ‘East meets West’ psychotherapeutic practice had me select the title of “travelogue” under which to bring my adventure to a close!

I started writing the book in April 2019: very nearly 3 years ago. Reading the manuscript again, taking in its complete arc, I can see the evolution of my thoughts and ideas, and hence my psychotherapeutic practice. This is both a good thing and a challenge. “Good”, because it supports that we are always a self-in-flux, changing and growing through our experiencing (this is not a surprise come from a Humanistic therapist, especially a Buddhist one). A “challenge” because how does one document a position on something if that position is shifting? This is where the “travelogue” section comes in – to help me convey the experiencing behind such principles to the therapist-in-training to whom the book is addressed.

It is timely that I am in a period of marking assignments and reading reflective journals of the trainees I work with on our Humanistic counselling and psychotherapy course; much mention is made of relinquishing ‘doing’ to trust their ‘being’. At the same time my own writing has had me consider how our ‘doing’ sculpts our ‘becoming’. All three modes need to be considered if we are to fully engage in “the preciousness of being free and well-favoured”, as the Dharma calls this human existence.

Doing is what takes us out into the world. Through our daily tasks, we take our shape and make meaning. It stimulates us, motivates us.

Being helps us connect to our essence and our nature. In stillness, we form relationship and connection to ourselves. Stimulation is reduced and we have an opportunity to nourish, re-ground, re-source. Doing needs being

Becoming is the coming together of our being and doing – it is the growth aspect, or what in the Humanistic tradition is referred to as ‘actualisation’. We could say that becoming is enhanced when doing and being are in dynamic balance.

Western psychotherapies tend to emphasise the horizontal unfolding of becoming; Eastern wisdom traditions, including Buddhism, emphasise the being aspect. One of the explorations in my book speaks to the therapist attitude taking on the quality of being, and how this holds the client’s becoming. I believe this is what Carl Jung was speaking to in his ideas on individuation – the expansion of self to Self through the attention to being as well as becoming. I have considered some of these ideas some years ago in a blog post, inspired by my time on retreat with the late John Welwood.

As I was reading student assignments and their reflective journals, it struck me how hard it is to stand back and trust clients have the potential to untangle the knots in their lives. I can see how much anxiety and self-doubt trainees hit in taking responsibility FOR the work and the relationship. And yet with time, the more we therapists can get out of our own way, the more scope we give the clients. The more we can trust OUR being is enough, the more effective the therapy space is for our clients’ becoming (and consequently, a shift toward responsibility TO the relationship)

The deeper I go into my explorations of a Buddhism-informed psychotherapy, the more I see the capacity of being for healing. Certainly, the practices and teachings of Buddhism see the process of becoming contributing to the endless cycles of suffering we meet as humans (referred to as samsara). What if both the therapist and client practiced simply being, would that be enough? Like the Gordian knot that responds better if we don’t try to untangle it. This is one aspect of a non-dual therapy – that the therapeutic space is a sanctuary where a client can learn to rest and see the doing of mind (thoughts) and body (behaviour) are not their true nature. “You are not your thoughts” is a common line in meditation teaching. Equally, we might be measured by our actions, but again they do not define WHO we are.

But is it as simple as ‘simply being’? Clients often ask me how this quality of being can be adopted and yet remain ‘functional’ and not negate impacting the world. There has been a lot of this questioning through the experience of the pandemic. Some have considered this period as having been an opportunity to step back and re-connect to a simpler life, to find being. Yet, can we live a fulfilling life without (at least) some doing?

Speaking with friends last night in our weekly meditation group Zoom, we discussed the Buddha’s teaching on the fourth paramita of “exertion”. As I have written about a few occasions on this blog, I have found the practices of the Six paramitas incredibly powerful in living a life with integrity (especially in the service of others). My friends and I unpacked what might constitute skilful effort: especially how we, culturally, tend to privilege ‘doing’ and give it high status. One aspect we talked about at length was how ‘busy-ness’ is actually consider a type of laziness in the view of the Buddhist Dharma. This can maybe help us keep the need for dynamic balance of doing and being in mind. Ensuring we have enough quiet time, stillness allows us to make informed decisions about our activity.

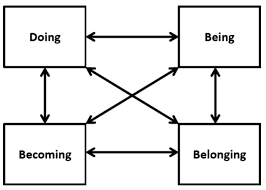

On pondering these questions, I came across the literature from occupational therapy in which the three dimensions of doing, being, and becoming are seen as integral to our well-being. OT literature adds a fourth dimension: belonging – through our doing, we go out into the world and connect with others, and thus we create community. My weekly meeting with meditation friends, my two days a week on campus teaching: I know how such moments of community also inform my becoming, my selfhood, and indeed life having meaning. This seems to be a useful 4-dimensional model: not to provide concrete answers as to how we live our lives, but rather as a ‘temperature check’ that might help us recognise where we are heading out of kilter (relative to personally held values). I immediately think of how the pandemic might have enabled more ‘being’, but our ‘doing’ has been curtailed to the expense of belonging

Not only is this useful to keep in mind as I write my “travelogue”; I am about to go into my second semester of teaching which each year has me co-teach a module on professional issues in counselling and psychotherapy. Philosophical inquiry is imperative to critical thinking and developing a practice not hinging on ‘right and wrong’ but rather building a rationale and reasoned argument. It is a module that can cause another spike of anxiety in our trainees, but the legal and ethical explorations are important nonetheless. I am sure this four dimensional model will be there in my mind.