This past week, I have been spending some time gathering my thoughts and resources ahead of a writing retreat over the Easter break. I have been working on a research project since last autumn, and having now analysed the interview data, I am ready to start preparing the research article…or so I thought.

I had asked a colleague of mine if she would take a look at the “findings” section I had written for my IPA study “exploring the experiences of humanistic practitioners: from counsellor to psychotherapist”. An experienced researcher herself, the invitation I had extended was to be the “critical friend” that I and this research needed. If you Google this term you will find various academic sites explaining the role of critical friendship as:

I had asked a colleague of mine if she would take a look at the “findings” section I had written for my IPA study “exploring the experiences of humanistic practitioners: from counsellor to psychotherapist”. An experienced researcher herself, the invitation I had extended was to be the “critical friend” that I and this research needed. If you Google this term you will find various academic sites explaining the role of critical friendship as:

- A professional sounding board

- A questioner who enable things to be seen in a new light

- A colleague that stimulates your thinking

- An independent, somewhat removed from your work but still understands it

And for me perhaps most importantly

- Someone who you trust and has the best interests of you and your work at heart, and is not afraid to be challenging

As we sat down over coffee this week, my critical friend pulled my draft from her bag – I felt an inner “gulp” as I saw her scribblings across the pages; I joked “at least you didn’t use red ink”. “No” she replied “I used green – for good, for “GO”!” We laughed, it broke the ice and I felt myself relax a bit. Even in the most trustworthy hands, exposing our work is like exposing our selves – especially when our writing is so close to our very being.

“Tell me about your motivation to do this research”, she asked. I paused, adjusted myself in my seat, took a swig of my cappuccino…I went down into my Self, reflected, searched back in my bodymind….indeed, where did the research question emerge from? I knew at that point that this was an opportunity for dialogue: something was not straightforward and so I asked my CF if she minded if I recorded our conversation. Something I have learnt through my professional and meditation practice arc is to settle back into bodymind and locate the answers from there; what a dear friend and colleague called an ‘access point’. It is a less heady point I go to for the answers these days, and being free to weave, to riff with a device recording the flow takes the pressure off to remember what I am saying; it releases me from conceptual mind.

What was clear as I searched for the answer to that first question was that my research design and research question were a little at odds; in essence, the design too particular to answer the general question. I was asking a very specific group of participants about a very specific scenario; and my dialogue with my CF was showing the holes in the work as it stood. Nothing unredeemable; I had options to interview more people – maybe across modalities, maybe from other training institutions. I could also locate this work in a different methodology: after all, I am someone who has trod the path from counselling to psychotherapy – a heuristic approach is just as valid if not more aligned than the IPA I had selected. But truthfully, did I really want to take any of these steps?

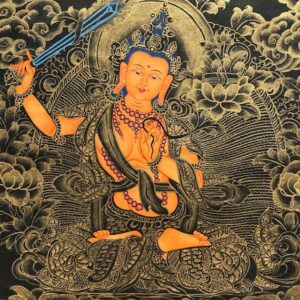

Rather than feeling demoralised, the conversation helped me to question and crystallise what I really wanted. The decision to complete a research study came much later than the desire that arose in me to write a book on humanistic psychotherapy. And, given this particular therapy approach arose from a culture of counselling*, I wanted to share my experiences of developing the ‘art’ from one that is holding and stabilising, to one that is deconstructing and effective. I often think of the Buddhist bodhisattva Manjushri as an archetype of the humanistic psychotherapist – their sword aloft, they kindly and cleanly cut neurosis, revealing the wisdom within. We might call Manjushri “the empathic challenger”. Indeed, themselves a “critical friend”.

Rather than feeling demoralised, the conversation helped me to question and crystallise what I really wanted. The decision to complete a research study came much later than the desire that arose in me to write a book on humanistic psychotherapy. And, given this particular therapy approach arose from a culture of counselling*, I wanted to share my experiences of developing the ‘art’ from one that is holding and stabilising, to one that is deconstructing and effective. I often think of the Buddhist bodhisattva Manjushri as an archetype of the humanistic psychotherapist – their sword aloft, they kindly and cleanly cut neurosis, revealing the wisdom within. We might call Manjushri “the empathic challenger”. Indeed, themselves a “critical friend”.

The humanistic view holds that we are all perfectly, imperfect. Each one of us has the potential for wholeness – if given the conditions for growth. The various therapeutic approaches within this broad umbrella include person-centred, transactional analysis, and Gestalt. These are the three main modalities we explore on our PGDip counselling course; and its not uncommon that students graduate feeling more comfortable practicing with a lens that remains “broadly humanistic” rather than taking on one of these core modalities more specifically. I was fortunate when I trained, as the Gestalt ‘glove’ fitted perfectly – maybe I was already an inherent “empathic challenger”? Probably my main challenge in fact was becoming gentler (especially to myself). A super internal critic; my learning edge was to befriend.

And so, this is the story I want to write next. I say “next” because my first book conveys much of that journey of ‘softening’ and befriending thanks to the Buddhist path. This current project is how I conceptualise the journey from counselling / counsellor to psychotherapy / psychotherapist. Writing up a research paper would have asked of me to take a particular position; to have interrogated the social construction around titles, qualifications, and status. Whilst this IS important (as many of my therapy colleagues will testify with regulatory issues like SCoPEd on the horizon), it is not my “thing”. My strength, my passion is to tell a story that may help others; especially helping others to help others themselves – my own bodhisattva name is Champ Sampe, or “bridge of maitri”.

It feels so relevant to be thinking of critical friendship at this time; almost synchronistic as I consider what sharpens the blade as we move from counselling to psychotherapy (distinct from any comment as to what title or qualification of “counsellor” or “psychotherapist” means – who is to say one is not the other in actual activity?***). We, as therapists, offer our clients a kind of critical friendship: a caring relationship through which one learns the edges of our imperfections – that applies to both parties in the room. I would say that is also my experience of being a supervisor AND an educator in a university setting. Whilst sometimes not easy to deliver skilfully, I try to walk the line that differentiates being “kind” from being “nice”. The latter is not helpful to those we serve.

I feel clearer about my writing retreat ahead. The day following the dialogue with my CF I spent the morning collating resources from our university library; what a delight to see my own book on the shelves! And now, piles of books on humanistic theory and philosophy lay on my study floor. What was to be a week on preparing a research paper is now devoted to idea generation, content mapping, table of contents drafting. There will still be a place for the voice of my research participants – I have no regrets about the time invested in interviews, transcribing, data analysis: all have brought me to here with a clearer vista and a sharper sword.

I feel clearer about my writing retreat ahead. The day following the dialogue with my CF I spent the morning collating resources from our university library; what a delight to see my own book on the shelves! And now, piles of books on humanistic theory and philosophy lay on my study floor. What was to be a week on preparing a research paper is now devoted to idea generation, content mapping, table of contents drafting. There will still be a place for the voice of my research participants – I have no regrets about the time invested in interviews, transcribing, data analysis: all have brought me to here with a clearer vista and a sharper sword.

———————-

*The humanistic view arose as a reaction to the prevailing psychoanalysis and behavioural therapies; with its roots in west coast America and the human potential movement of the 1960s

**The controversial Scope of Practice and Education is intended to “set out the core training, practice and competence requirements for counsellors and psychotherapists”

*** This was one aspect in the research data that my participants agreed on – they are not separate and yet they are different