As I sit to write this morning, I cup my hands around my coffee and cast my eyes out the window. I have a beautiful view of the Downs, the sun is shining, I feel the warmth of my coffee, I take a sip. Discrete moments in experience. Awareness seems to take over, and with that a shift from the contents of experience (the sight of the view, the warm touch, the bitter / milky taste) to experiencing itself, a deep sense of contentment and openness arises. Everything, including me, arises in awareness – no separation. This is stepping into Sacred World – hard to put words on, a sense of experiencing outside of time, outside of space along with a deep appreciation.

Be under no illusion – this is not to suggest I am blissing out! Focus in on my coffee cup in the picture and it hints at the present life stressors (I often select my coffee mugs based on my mood). I have not slept well for what seems like eternity, I have a lot of work to do before the end of the week, and two busy teaching days on campus ahead of me. But the shift to awareness clarifies what is here, what is not. Each thought becomes another content of experience: like the sight, touch, taste, just another wave.

Be under no illusion – this is not to suggest I am blissing out! Focus in on my coffee cup in the picture and it hints at the present life stressors (I often select my coffee mugs based on my mood). I have not slept well for what seems like eternity, I have a lot of work to do before the end of the week, and two busy teaching days on campus ahead of me. But the shift to awareness clarifies what is here, what is not. Each thought becomes another content of experience: like the sight, touch, taste, just another wave.

Much of a Buddhism-informed psychotherapy – the theme I am writing about in my first book – works with these ideas. It posits that suffering and distress stem from our belief that we are a separate, solid self (rather than a flux of experiencing – our senses, our mental activity, and our interpretation-of / attachment-to our mental activity). The aim of a Buddhism-informed psychotherapy therefore is to help the client come to know an alternative; to become aware of direct experience (as distinct from the stories we tell ourselves about what is being experienced).

Last week, I was working with our first year students in the afternoon experiential workshop. We were discussing their ‘learning edges’, and how we could meet their aspiration “to be more embodied”. Knowing my approach, they were keen to understand how they could ‘dip their toes in’ over the next 6 weeks I would be working with them. They are training in the Humanistic tradition of counselling and psychotherapy – a paradigm that already holds “the here and now” in high regard. Indeed, Fritz Perls co-founder of the Gestalt tradition said himself that “awareness in and of itself is curative”. So, what might a Buddhism-informed approach offer as ‘value-added’?

Humanistic: awareness OF experience; a self that is able to know the contents of experience; to take in more of the experience at hand

Buddhism – experience arising IN awareness; there is no separate knower of what is known, just experiencing

If that is experienced as mind-blowing, this is good news!

Of course, experience OF suffering, distress, or indeed trauma IS very real, and yet if we look for “who” is experiencing it, the experiencer is elusive. How do reconcile this?

All the different modes of Western psychotherapy point to the importance of the relationship between therapist and client. Whether it is the offering of a healing presence or a safe neural network upon which a client can attach, all agree this happens in the relational space. Many models also point to the value of regression, or re-creation of an early stage of experiencing in the safe space of the therapy room. A therapist helping the return to an experience of initial wounding and providing the ‘good enough’ holding not available back then, things can be experienced differently: why therapy is often talked of as re-parenting.

I made mention of “Sacred World” last week: the inherent wholeness of self, other, world (and cosmos). I see this as a natural extension of Martin Buber’s notion of the “I-Thou”: the full, direct, mutual relation between beings (as opposed to a subject, “I” relating to an object, “it”). Sacred World, sacred relating – the collapse of duality, separateness. Anyone who has experienced this might find themselves short of words of description, but there is often a sense of being outside of time, outside of space. And if so, how can we be in the here, in the now? I call upon psychotherapist Daniel Stern:

“Objectively, present moments last from 1 to 10 seconds with an average around 3 to 4 seconds. Subjectively, they are what we experience as an uninterrupted now”.

“Objectively, present moments last from 1 to 10 seconds with an average around 3 to 4 seconds. Subjectively, they are what we experience as an uninterrupted now”.

Maybe we could consider the art of psychotherapy to occur in moments outside of the three conventional aspects of time? Clients will bring memories of the past, anxieties about the future to the present moment of the therapy room. Maybe, as hinted at in Buber’s I-Thou and in Stern’s words above, healing happens in another dimension: one in Buddhism referred to as “now-ness”, or the fourth moment. Chogyam Trungpa offers this to differentiate between the present moment and now-ness:

“The present is the third moment. It has a sense of presence. You might say, “I can feel your presence.” The fourth moment is a state of totality. Basic awareness is taking place which doesn’t need any particular reassurance as such. It is happening. It is there. You feel the totality. You perceive not only the beam of light from the flashlight, but you see the space around you at the same time. The fourth moment is a much larger version of the third moment.”

A fourth moment, the totality of experiencing without reference point. Last week I introduced the Svabhavikakaya as a Buddhist teaching speaking to this totality; the “fourth kaya” that encompasses the three kayas. Inspired by my time with the first year trainees, I have been wondering if this is a useful way to explore the alchemy of healing within “now-ness”.

Three kayas in psychotherapy

On the training courses for counselling and psychotherapy, we encourage the students to reflect upon the process in the therapy room across self, other, and the relationship. To me, these map onto the 3 kayas in the following way:

The Self and Other of the therapist and client are the physical manifestation of the Nirmanakaya. Traditionally, this kaya is sometimes called the gross body and is said to manifest physical form as skilful means i.e. in response to what beings need. If we consider the self to be a constellation of experiences (of the sense perceptions and ‘mind’), it can be thought of as a gateway through which the localisation of consciousness (that we call ‘self’) gets to be an actor in the world. We can know our experience because we have a physical form and shape. A therapist, through knowing their own experience – what I call a vertical relating – can help a client know their own direct experience.

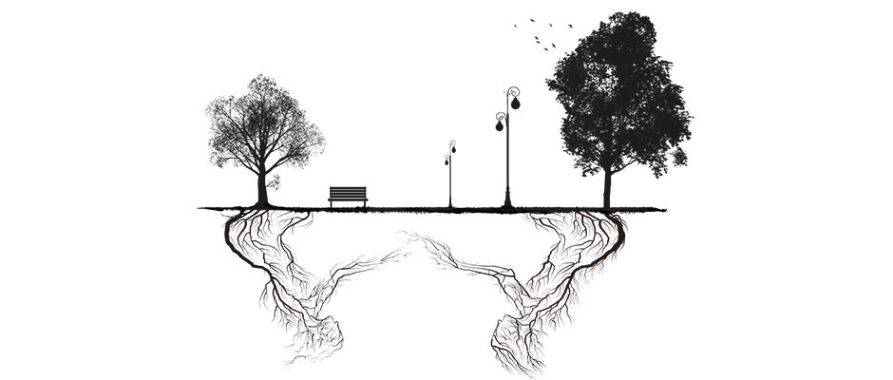

I propose the relational between as the Dharmakaya – a space without form, substance, or concept of any sort. In psychotherapy writings, we might come across the notion of the container. Although the container evokes a physical form, the real magic of the container (like an alchemical vessel) is the facilitation of the process within. The space of the relational between might be thought of as empty – not in a void like way, but more in line with the Buddhist teachings on emptiness – vivid and alive with potential, with clarity and knowing.

This empty-clarity allows the play of therapy – what the Dharma would term the Sambobhakaya. Sometimes this is called the subtle body, but here it is the body of communication, the play of energy and experiential wisdom. Traditionally, this kaya is the bridge between the formless and the material. We could liken this to the mysterious healing that happens between therapist and client in the relational between.

We could see the the fourth kaya of Svabhavikakaya as the realisation that none of the above are separate; and that all the three kayas are simultaneously present or in otherwords, “now-ness”. How is this useful for me teaching trainee therapists? There is something about putting into words (for me, not said explicitly) the trust we can have in the relational between: what has been called variously the subterranean between therapist and client, or the notion of M/We in the interpersonal neurobiology literature*. As I watch the first year trainees grapple with the art of psychotherapy, I can only encourage non-doing and trust their being presence as healing.

The trust in letting be, the less is more, the hands-off…it can take some ‘doing’ to enter into ‘being’. I have been at that edge, one that can feel like a giant precipice. One offering I make to trainees is to get familiar with the direct experience of their own being. This is where the meditation practices of the Buddhist path can provide powerful support in developing vertical presence to enhance horizontal relating. In my forthcoming book, I recount the power of practices such the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. The body, feeling tone, mind, and all of experience as objects of meditation also maps with the four kayas.

The more I move my practice from the cushion out into the world, into relationship, I value the descriptions of experience the Buddhist dharma points to. Working with the four kayas in my life, I see the repeating patterns akin to fractals in mathematical descriptions of nature. All experience is an integrated wholeness, arising simultaneously through the aspects of space, form, and communication between the two.

Next week I hope to share some ideas on a third and final aspect arising from feedback on my book: that of how an understanding of karma is helpful for the psychotherapist.

___________

*It is interesting to me to consider how Daniel Siegal refers to the three aspects of relationship, brain and mind – they too seem to align to the description offered by the three kayas, and a consciousness of the ‘between’.