It’s not uncommon after a day of working with clients and meeting with supervisees that I sit mulling over how therapy works. My teaching role also allows such reflection; I recently wrote about the nature of change and some thoughts that came to me whilst preparing new teaching material for our MSc psychotherapy course. Today I write this post ahead of my own supervision session; wondering what might be going on for a client in our relationship, how I am experiencing them and what it might be telling me about the client’s familiar experience of the world and others in it.

Viewed from the therapist’s chair, how the client is blocked in their life and what they are doing to contribute to those blocks is clearer than to the client themselves. Probably you too will have experienced this in your everyday life – to witness the struggle of loved ones, and see a seemingly obvious way out that they cannot see. But giving that feedback can feel incredibly difficult. And as stressed in the Humanistic tradition, long lasting change can only happen when someone sees and experiences for themselves the block; AND finds their own way through – we cannot tell someone what to do if we were in their shoes. Telling someone what to do firstly takes away the need to fully feel the experience (and there is a lot of wisdom contained within feeling the block); telling others the way out also fosters dependence; as therapist, I want clients to be autonomous and find their own power. Importantly, it also undercuts the view that we are all fully resourced and have the capacity to find solutions and our own way in the world.

And so it is one of the biggest challenges a therapist can meet in their practice – conveying what they see at the root of a client’s complaint and how the client themselves is perpetuating the situation. It is not simply telling them what we see, and then telling them not to – or as my dear colleague Jamie used to love, advocate tongue-in-cheek “stop it” therapy! Furthermore, it is only our subjective experience of the client – just because we experience them a certain way does not make this a truth. As a therapist, we also need to know our own process and whether we experience a client in a particular way because of our own emotional propensities in relating – known in the field as “my stuff”. But even owning our subjectivity, feedback in service to the healing process remains difficult and can require some courage. As one of my colleagues says “how do you tell a client what they don’t want to know in a way that they can hear it?”

And so it is one of the biggest challenges a therapist can meet in their practice – conveying what they see at the root of a client’s complaint and how the client themselves is perpetuating the situation. It is not simply telling them what we see, and then telling them not to – or as my dear colleague Jamie used to love, advocate tongue-in-cheek “stop it” therapy! Furthermore, it is only our subjective experience of the client – just because we experience them a certain way does not make this a truth. As a therapist, we also need to know our own process and whether we experience a client in a particular way because of our own emotional propensities in relating – known in the field as “my stuff”. But even owning our subjectivity, feedback in service to the healing process remains difficult and can require some courage. As one of my colleagues says “how do you tell a client what they don’t want to know in a way that they can hear it?”

Importantly, such feedback can only take place having established a strong working alliance – the therapist and the client need to be on the same side. The client has to know we are there with our empathy, our compassion; the therapist has to know that the client is willing and open-minded. Mutual trust creates a bond, and a commitment to the relational space – no matter how bumpy a ride. The relationship becomes a true alliance however only when the tasks of therapy have been established together. On the side of the therapist, this is a clear communication of what the work of therapy entails. This includes the knowing of their own frame, and explaining this to the client. I have found this important, especially in helping my clients understand that ‘talking therapy’ is NOT ‘talking about’ problems; nor is it about me finding solutions. In fact, it’s not about problems nor solutions but exploring the lived experience of being a human being.

We might call some of this initial process ‘psychoeducation‘, but this only goes so far. Helping a client have a working knowledge of their mind and how therapy aims to target those ‘cogs and gears’ provides a basis, but this is not about teaching. In fact if I feel my Teacher head coming into the room, I give myself a little talking to and ask the client to watch out for me trying to be clever! Far more effective is for me to model how to ‘explore the lived experience’. As I listen to their stories, I am tuning into my experiencing; and at times I offer how their stories affect me (emotions) and where this is having an effect (in my body). Over time, it is amazing how they begin to adopt some of this – like a call and response:

“As I hear you speak of your brother I notice my sadness. I feel a welling up in my chest, something full and expanding”

“Yes, there is something stirring there. I hadn’t noticed it”

I shared with you a few times on this blog the importance of the Feminine and Masculine blend. In this case, therapy requires the meeting of the bottom up experiencing (feminine receptive quality) and the head down theorising (masculine thinking quality). I appreciate the Gestalt theory within the “cycle of experience“. As I sit in the room and feel into my experiencing, I get curious about the quality of the contact between my client and I. I notice when I ask a question such as “how does that feel to you” and it is greeted with a reply “I think…” that the client has deflected from feeling to thought; or, I might notice when a client projects what they are fearing I am thinking.

Now, I can tell them what I experience. But more powerful is to come up with an intervention that helps them experience, and thus ramping up awareness of their whole being (and not just their well-honed thinking muscles). Interventions are important – it is the therapists ‘armoury’ in interrupting and disrupting a clients habits of being. Interventions are, in my experience, also the way to walk that tension between empathy and challenge. But before we can implement an intervention, it can help to form a clear sense of the dynamic playing out in the room – and I have found metaphor a great precursor to intervention, or ‘experiment’ in Gestalt terminology. Perhaps some examples will help illustrate this…

Push and Pull.

When thinking about this felt dynamic, it came to mind that there are a few nuanced versions a therapist and client might experience. In a first variety, it can be a sense of an alternating pattern across sessions, one in which I get a sense the client idealises me one week, next week shuts down, knocks me off the pedestal. All good, all bad. I find myself feeling “chuffed” and then “confused” – a bit like when we have been playing with an adorable kitten, tickling its tummy and then out of the blue “swipe”; “what happened there?” Closeness, distance; open, shut. In a second variation, a sort of competitive feel begins to manifest in the room. It might be more accurate to feel this as ‘tit for tat’ rather than push and pull. A sense that there is “one-upmanship” playing out. I was once working with a social worker where this competitive sense was evoked for me. She would often speak of “health professionals like us”, and would correct my observations or reflections. I could see and experience their desire for my esteem. When we find ourselves in such a relational field, a therapist can offer an ‘invitation’ to play, to experiment in service of the dynamic becoming more alive in the room. With the social worker, I suggested whenever either of us felt a ‘tug’, we might pick up the end of the rope I had as a prop in my therapy room. We ramped up the experiment by deliberating playing ‘tit for tat’ – I invited the client to contradict everything I said, and to feel into how that was in the here and now, in service of unlocking understanding the there and then of when this strategy was developed and needed to survive. To work with ‘push and pull’, I might suggest to a client we hold a ball between us, pushing each other back and forth in tune with how close we felt while we spoke. Both these experiments exaggerate and amplify what is already playing out, outside of awareness; or making the implicit, explicit.

Hide and seek

Hide and seek

With this relational dynamic, in order to ‘find’ the client I sense I am having to go over the ‘mid-line’ in the space between us, or what in Gestalt we call the contact boundary (between self and other). That feeling might arise for me when on inviting a client to share how they feel about a situation they are describing, there is a deflection – in the form of a change of topic, or deferring to talking about more of the content of the story rather than sharing its impact. One experiment I used with a client recently was marking a line out on the floor between us. I invited him to position themselves relative to the line to indicate where they felt there were relative to me, in ‘us’. Furthermore, where was I, and ideally where would they like me to be? Further away, closer to; and then, where would they like to go once I had moved? Other experiments here could involve changing the orientation of our chairs, to be side by side and slowly moving toward face to face. Another version is to “titrate” eye contact: sitting face to face but with closed eyes – how is that? Now opening them but averted downward – what is it like to like to bring me into their awareness. As with all experiments, it is important to proceed slowly, feeling each increment directly; and to also have ways of graduation, slowly increasing their intensity and therefore felt impact.

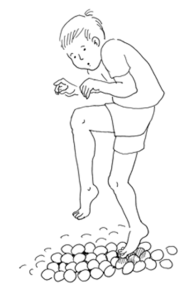

Walking on egg shells.

Walking on egg shells.

A final example might be one where I feel quite cagey and hesitant; I know what I am experiencing, feeling, and yet don’t feel ‘brave” enough to share. I realise I am going along with a client’s narrative, confluent. This can come with a sense of a client’s fragility (not wanting to hurt) but for me personally, I find it harder when its about a felt sense of a client’s anger or rage, a sense I might inadvertently burst a bubble. This is one example of how our own material can mingle with that of the clients. For such occasions, I bring in the “elephant in the room” – a plastic model a friend once bought me. I ask if the client too can feel something else is here with us.

Key to all of the above, and indeed any relational intervention is to challenge the process, not the client. To challenge the withdrawing (for example) and not give any kind of sense if it being ‘wrong’; to arouse the curiosity as to how it might once have been useful, helpful, protective. “What is gained by withdrawing?”

Furthermore, I need to own my part in the situation – afterall, relating is a verb, and it takes two! “What is it I just did / said that lead to you feeling the need to withdraw?”

I will take some time in a future blog to explain more about the use of experiments in Gestalt psychotherapy – it is worth taking some time to demystify this form of intervention, as its often a hurdle training clients need to ‘get over’. It can feel like we are ‘doing’ something to the client and thus like we are going against a key principle of the Humanistic tradition i.e. letting the client lead. Once we understand, as I mention above, that it is simply a spontaneous act to raise awareness some of those concerns can dissipate. More soon!