I mentioned a few weeks back how being in groups can offer a useful experience in which to explore aspects of ourselves; to look at dynamics that feel familiar to us – literally familiar, as they often originate in the family. I had the privilege of working with a group of trainee therapists at the weekend, taking them through the main principles of Gestalt therapy and witnessing them in relationship. A group of some 20 individuals, by the end of the weekend they were experiencing how the group takes on a form of its own: the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

I mentioned a few weeks back how being in groups can offer a useful experience in which to explore aspects of ourselves; to look at dynamics that feel familiar to us – literally familiar, as they often originate in the family. I had the privilege of working with a group of trainee therapists at the weekend, taking them through the main principles of Gestalt therapy and witnessing them in relationship. A group of some 20 individuals, by the end of the weekend they were experiencing how the group takes on a form of its own: the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

Group working is one of the main reasons I gravitated to the Gestalt psychotherapeutic frame during my training. Gestalt values highly group process to help individuals move towards ‘wholeness’: to bring awareness to the experience the Self is having in the here and now, the present moment. Of course, this can be facilitated in 1-2-1 therapy, the therapist providing prompts to bring the client in to the present and share what is happening in the relationship, and how it is being experienced. The beauty of group work is that the group and its members take on a transferential quality – we get to meet our Mothers, our Fathers, our siblings, our teachers…and, often outside of our awareness, our Selves that are projected on to other group participants. Gestalt invites a couple of ways that offer the opportunity to catch hold of what is being experienced – slowing down to check inward, and an ‘experimental’ approach that helps to magnify experience. We used a series of exercises over the weekend: from those designed to bring more contact to the inner experiencing of the body, mind and environment; through to exercises inviting different parts of self to come forward and exaggerating some of their qualities and needs; and on to those that take the relationship with self in to the relationship to others.

As those exercises unfold, the energy in the group is in constant flux: people are having frequent insights, contacting emotions unknown or long held back. As a facilitator, the main role is to hold the space. It can be very hard to not step in – to rescue people in pain or to point out the process that might be blocking a person or how someone’s way of being and acting is causing another person pain. We have found in the years of running these sessions a mix of experiential exercises and ‘lecturettes’ (short explanations of theory to hang experience on) is an effective approach. Our only role is to provide the safe space for people to ‘play’ within – to act out, to rupture, to repair. Gestalt, like all the humanistic traditions of therapy, respects the individual’s agency and responsibility. It also trusts that people WILL find the way towards growth – however tempting it is point out what we see, we know we have to let the penny drop for the individual. You might recognise how often people try and give advice – but it is only when we see or feel something inside of us that things change: in Gestalt we call this the “a-ha” moment, something shifts inside and we see things in a clearer way. No-one can force “a-ha” moments on others. As I shared with the group at the weekend, “you can’t push the river”.

As those exercises unfold, the energy in the group is in constant flux: people are having frequent insights, contacting emotions unknown or long held back. As a facilitator, the main role is to hold the space. It can be very hard to not step in – to rescue people in pain or to point out the process that might be blocking a person or how someone’s way of being and acting is causing another person pain. We have found in the years of running these sessions a mix of experiential exercises and ‘lecturettes’ (short explanations of theory to hang experience on) is an effective approach. Our only role is to provide the safe space for people to ‘play’ within – to act out, to rupture, to repair. Gestalt, like all the humanistic traditions of therapy, respects the individual’s agency and responsibility. It also trusts that people WILL find the way towards growth – however tempting it is point out what we see, we know we have to let the penny drop for the individual. You might recognise how often people try and give advice – but it is only when we see or feel something inside of us that things change: in Gestalt we call this the “a-ha” moment, something shifts inside and we see things in a clearer way. No-one can force “a-ha” moments on others. As I shared with the group at the weekend, “you can’t push the river”.

…but you CAN give it feedback on how it is flowing! But that is not easy work for the group. On the final segment of the weekend, we spend the afternoon in group process. We first set up a ‘sculpt’: an exercise where people shape their experience in the group using a physical metaphor. I won’t give the game away as to what we exactly do – there might be future trainees reading this after all! But let me give you an example – we might set up the room like a maze or obstacle course and then ask the trainees to position themselves in that space that describes how they experience their position in the group. You get varied responses: people go to the middle, they get right “in the thick of it”; you might get others who dare not enter the maze, “its not safe to be in”. We spend an hour helping the trainees explore what is going on for them, what is blocking them, their beliefs about how they are and how they are perceived, how they view others, what is safe, what would be taking a risk. It can invoke a lot of emotion: people begin to realise what stories they hold – stories that have been constructed long ago to keep them safe but now block them to making authentic choices and satisfying relationships.

For me, the most fulfilling (and revealing) part of the weekend is always the final group processing: we all sit in a circle with the only instruction being “exploring your experience of the group”. A good amount of time is needed to let things unfold: sometimes that process only just begins in the time we have, sometimes it erupts and remains unfinished, and sometimes it erupts and resolves. In the facilitator chair, I have to stay in contact with my seat, my centre, my hara. It becomes easier for me to partition out what is my script (how I could get bent out of shape, jump up and get involved), and what is centred and holding (how to stay, to not reach up and out). I have to keep coming back to trust in the trainees ability to do this dance themselves. It can be frustrating to watch them ‘not get it’ when it is SO clear to me what is going on: who is rescuing, who is projecting, who is antagonising, who is defending, who is being oppositional, who is being vulnerable, who is focused on self, who is focusing on others. I watch the quiet ones – so much is said in silence, body language never lies. All we as facilitators can do is offer occasional process comments: “as I sit and watch things unfold, I have noticed people communicating on a few different levels: some of you are providing commentary on the group as if its a third object; some of you are offering your personal experiencing as if in to the space; and some of you are offering your experience in direct communication with another. Just notice where you are at, and how it feels to have heard these thoughts from me”. When I was a trainee, we used to call these observations “process bombs”! As comments can often be taken as criticisms: fodder for retroflection (where someone turns the emotional reaction in on themselves) or for projection (where someone throws the emotional reaction out to someone else). It is fascinating to see how differently people take neutral information and load it according to the stories they hold. And, how small groups and alliances build and break down when direct communication and dialogue are somehow managed.

For me, the most fulfilling (and revealing) part of the weekend is always the final group processing: we all sit in a circle with the only instruction being “exploring your experience of the group”. A good amount of time is needed to let things unfold: sometimes that process only just begins in the time we have, sometimes it erupts and remains unfinished, and sometimes it erupts and resolves. In the facilitator chair, I have to stay in contact with my seat, my centre, my hara. It becomes easier for me to partition out what is my script (how I could get bent out of shape, jump up and get involved), and what is centred and holding (how to stay, to not reach up and out). I have to keep coming back to trust in the trainees ability to do this dance themselves. It can be frustrating to watch them ‘not get it’ when it is SO clear to me what is going on: who is rescuing, who is projecting, who is antagonising, who is defending, who is being oppositional, who is being vulnerable, who is focused on self, who is focusing on others. I watch the quiet ones – so much is said in silence, body language never lies. All we as facilitators can do is offer occasional process comments: “as I sit and watch things unfold, I have noticed people communicating on a few different levels: some of you are providing commentary on the group as if its a third object; some of you are offering your personal experiencing as if in to the space; and some of you are offering your experience in direct communication with another. Just notice where you are at, and how it feels to have heard these thoughts from me”. When I was a trainee, we used to call these observations “process bombs”! As comments can often be taken as criticisms: fodder for retroflection (where someone turns the emotional reaction in on themselves) or for projection (where someone throws the emotional reaction out to someone else). It is fascinating to see how differently people take neutral information and load it according to the stories they hold. And, how small groups and alliances build and break down when direct communication and dialogue are somehow managed.

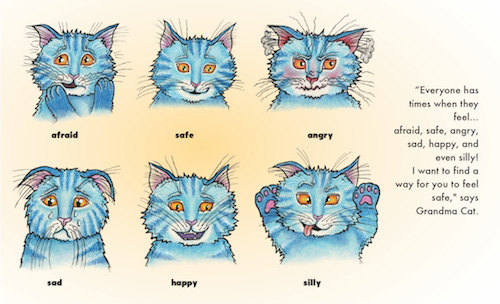

In my experience, groups find it easier to share their sadness and vulnerability to the group, and their love and compassion for one another inresponse to hearing those expressing vulnerability. Less easy, and we know this from life, is to feel safe communicating our annoyance and irritation with another directly – and then, for the group to accept this emotion and someone’s right to express it. The more that a group can welcome ANY emotion, the more likelihood that individuals can trust the authenticity of relationships. But this process needs time: and sometimes there can be a sense of unfinished business, things left unspoken, an elephant in the room can remain.

Of course, there is ALWAYS unfinished business in any relationship. For me, it becomes about what is tolerable. So far in my teaching and facilitating role at the University I have observed several paths that the group take after this experiential weekend – they all find their way, in some way…it might not be my way, but its their way. And whatever the way they find, I am always left with feeling honoured to have been a small part in that journey.