How mindfulness meditation helps me be a better therapist to my clients

In the coming months I am delivering mindfulness workshops to practitioners within the counselling and psychotherapy profession. It is incredible to witness the growing interest to mindful living generally; I am especially pleased to see my profession placing value in the practice of meditation. There are benefits in teaching our clients how to use mindfulness: certainly there is a lot of research emerging as to how meditation may combine with therapy to produce more effective and long lasting change and / or symptom management. I am sure I will return to this topic in a future blog post. For today however I offer a personal perspective as to how I think my meditation practice (as therapist) benefits my clients.

I’ve been giving a lot of thought towards what (up until now) have been my two paths – those of my meditation and my therapeutic paths. I say ‘up until now’ because I am witnessing a merging: personally and professionally. I remember sharing with my own therapist about 5 months ago that I aspired to “truly being a Buddhist” and to have that cradle everything else in my world. That vision is coming to fruition: I see how my meditation practice underpins my values and way of being in the world; and that provides the support of my work as therapist (as well as other roles such as partner, daughter, friend).

I’ve been giving a lot of thought towards what (up until now) have been my two paths – those of my meditation and my therapeutic paths. I say ‘up until now’ because I am witnessing a merging: personally and professionally. I remember sharing with my own therapist about 5 months ago that I aspired to “truly being a Buddhist” and to have that cradle everything else in my world. That vision is coming to fruition: I see how my meditation practice underpins my values and way of being in the world; and that provides the support of my work as therapist (as well as other roles such as partner, daughter, friend).

My home retreat a few weeks back gave me the opportunity to reflect on living one, common path. I used the time and space to formulate my intentions, specifically as to how I can help others. What really came through to me is how important the actual practice of meditation is (aside from the ethics and compassion practices that are central to life as a Buddhist).

Stabilising the mind

The essential practice in my meditation ‘diet’ is that of breath-awareness, or ‘shamatha’ (sanskritfor ‘calm-abiding’). Using the breath as my object for my mindfulness, I sit and bring single-pointed attention. The phrase ‘calm-abiding’ doesn’t mean a goal of peace and tranquility (or that would mean I ‘fail’ 8 or 9 times out of 10!). Nor is the measure of the practice how well I hold on to the breath. Rather, I direct my attention to the breath as an anchor to the here and now, and if when I get distracted I label it with ‘thinking’ and I come back to the breath. Some days it is relatively straightforward and my experience is quite peaceful and easeful; on other days my mind is distracted and it feels a struggle – I lose the breath, I bring my mind back to it. The ‘calm-abiding’ is the attitude to the oft the tug-of-war. I practice ‘equanimity’ or non-judgement of my experience. Whether easeful of requiring constant effort ‘to come back’, through sitting (over time) my mind slows, gaps between each successive thought appear and lengthen. A period of mediation is often likened to having a jar full of muddy water which settles as we leave it to rest. Letting my mind settle, having my thoughts slow down allows clarity (the mud rests at the bottom with clear water on top). In this space I find that insights relating to my own process emerge. I start to make links between my state of mind, feelings, emotions and events in my life.

Developing the watcher

Another critical practice for me has been that of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. In shamatha, the object is thebreath: in the Four Foundations 1) I begin with the object of the body noticing any physical sensations; 2) I move my attention to the feelings that come up and labelling them simply pleasant, unpleasant or neutral; 3) next my mindfulness is directed to the mind itself, watching the thoughts that arise; 4) finally mindfulness of the contents of the mind asks for a linking of the arising thoughts within aspects of Buddhist teachings. It provides a methodical way to practice applying my mindfulness across different processes that ordinarily I’m not aware of (because they are going on all the time underneath daily concerns). When I teach this practice to others, I describe how its a bit like watching our experience unfold on a screen from a seat in a cinema. It is a beautiful analogy because it implies an ability to stand-back: to be fully contacted with our experience yet not enveloped by it. Developing the movie-goer or ‘watcher’ (without entering the drama being played out on the screen / in the mind) helps build the quality of equanimity (upeksha in sanskrit). This is probably close to what Freud referred to as “evenly suspended attention”.

Self-care

How often do we really take time out? My 30 minutes each morning is a very personal space, real ‘me-time’. Simplysitting still without an outcome is one thing that helps me keep my batteries charged. OK, each meditation is not all peace, calm and tranquility – it is not an easy practice: yet with time, the effects are become clear. Since I have been meditating (five years now) I sleep better, I understand more what is going on behind my feelings and emotions, and I am less reactive in relationships. Life takes less out of me when I make the time to meditate.

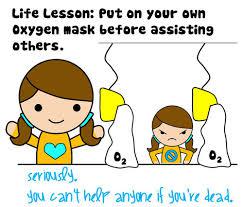

Rest and self-care are so important. When you take time to replenish your spirit, it allows you to serve others from the overflow. You cannot serve from an empty vessel.

― Eleanor Brownn

putting-on-your-own-oxygen-mask-firstThese first three aspects are really about ‘me’ – how meditation aids Helen as a person. In a modern day interpretation of the Buddhist teachings is the example of the oxygen mask – we can only help others once we have seen that our own needs are met. This is not some narcissistic statement – we have to be in sound health (physically and emotionally) to serve others. This is especially true in the helping professions. When seeing a number of clients per week and helping them with difficulty emotional struggles, my meditation keeps me grounded and ‘fit to practice’. Counselling and psychotherapy is known to be a profession with a high rate of burnout.

Adding value to the therapeutic relationship

Having stabilised my own mind and taken care of my self, I am ready to enter the room with a client undistracted and ready to be there for them, totally. Much of the therapeutic literature (especially the research of the Humanistic approach) speaks of the importance of ‘presence’. Therapeutic presence involves being fully in the moment with a client on a multitude of levels – physically, emotionally, cognitively, and spiritually. It is presence that helps me be fully open to the client’s world yet remain in touch with my own experience. Therapists rely a lot on their congruence – the ability to detect what is going on internally and to then be able to express this in real time to the client. Much feedback about a client’s way of being can be generated if a therapist is able to tune in as to how that client is impacting on them. The key for me is how mindfulness meditation (alongside my personally therapy) helps bring clarity to my own process and enables me to separate out my stuff* from the client’s.

Having stabilised my own mind and taken care of my self, I am ready to enter the room with a client undistracted and ready to be there for them, totally. Much of the therapeutic literature (especially the research of the Humanistic approach) speaks of the importance of ‘presence’. Therapeutic presence involves being fully in the moment with a client on a multitude of levels – physically, emotionally, cognitively, and spiritually. It is presence that helps me be fully open to the client’s world yet remain in touch with my own experience. Therapists rely a lot on their congruence – the ability to detect what is going on internally and to then be able to express this in real time to the client. Much feedback about a client’s way of being can be generated if a therapist is able to tune in as to how that client is impacting on them. The key for me is how mindfulness meditation (alongside my personally therapy) helps bring clarity to my own process and enables me to separate out my stuff* from the client’s.

Daniel Siegel writes beautifully on the topic of how mindfulness can enhance the therapeutic process, and I have found what he offers with the acronym of PART speaks to my experience with clients:

- My presence is a way I remain grounded in myself. I am able to locate my own needs and be undistracted with a client

- Settled, I am able to attune with the client’s internal experience and their world

- There is alignment, two people in a room opening to each other brings resonance – we recognise our shared humanity and begin to influence each other’s state of being**

- My client feels fully heard, fully felt – trust between us is nurtured which as Siegel explains is the starting point for true interpersonal integration

Neuroscience is establishing the changes in brain structure and function that come with regular mindfulness training – and this scientific basis is one reason why the health professions (including therapists) are keen to use meditation for themselves and reassured in recommending it to patients and clients. I certainly find it invaluable for my therapeutic counselling work. However, I would urge some caution: I believe we (the practitioner) need a strong personal mindfulness practice before we attempt to use it in our work, or indeed teach our clients to use it. As I mentioned earlier, whilst it is a straightforward practice, it is not an easy one. Having our own experience of the pitfalls and challenges is vital if we can attune to the client’s attempts. I have also found that meditation can bring up ‘stuff’, which while useful material for therapy it is again advisable to have experienced a version of this ‘stirring up’ ourselves so we can truly get alongside our clients.

I’d love to hear feedback on these ideas and others’ experience of using meditation as a grounding platform for their work, so please get in touch.

*Stuff – technical term in the trade meaning baggage, personal history, unresolved issues. For example, if I am sitting opposite a client and notice sensations of anger, I need to be clear whether it is my own anger or that anger is in the room possibly coming from a client’s process.

**Maybe to the degree where the therapist-client experience Martin Buber’s “I-Thou” or what is called “relational depth” in some psychotherapeutic literature