I have just returned from a trip to the US. Part “big birthday” celebration; part tour of Buddhist friends old and new; part retreat. Ever since completing my meditation teacher training there 11 years ago, the city of New York has been something of a spiritual home for me. The yearlong immersion in Buddhist study and practice carries incredible significance in my life to date: a real consolidation of the commitment to the path, and experiences that cracked my heart open. What with my book coming into being this year, and its roots firmly in that initiation of 2012, the visit and reunion with dear ones felt timely.

I have just returned from a trip to the US. Part “big birthday” celebration; part tour of Buddhist friends old and new; part retreat. Ever since completing my meditation teacher training there 11 years ago, the city of New York has been something of a spiritual home for me. The yearlong immersion in Buddhist study and practice carries incredible significance in my life to date: a real consolidation of the commitment to the path, and experiences that cracked my heart open. What with my book coming into being this year, and its roots firmly in that initiation of 2012, the visit and reunion with dear ones felt timely.

It has been nearly four years since I visited the US; nearly four years since I have flown long haul. Experiences that seem both different yet familiar. Walking the streets of Manhattan, again familiar yet different. Was it NYC that had changed? Was it me? I watched my mind as it tried to reconcile something of a dissonance between the rational and the embodied felt sense of it all. I enjoyed my time in the city; but I was also ready to leave when part 2 of the trip called.

Not but, rather ‘and ready to leave.’ Fritz Perls, founder of the Gestalt approach to therapy, considered the use of the word ‘but’ to discount the first half of a statement. It speaks to a key tenet in Gestalt – that there are always polarities in operation. Rather than ‘either / or’, we recognise the ‘both / and’ quality to experience. I had many opportunities to ponder this on my trip: the excitement to be back AND the sadness it brought up. Nostalgia.

As my wife and I collected our hire car to begin part 2, I felt sad and relieved to leave Manhattan behind. I watched the skyline disappear into the background as we hit the highway and headed toward Pennsylvania. Part 2 came in two parts*: re-uniting with my current sangha in two chapters. The one and only time I have been to PA was to receive the transmission into the Vajrayana (in 2019). The friends I was about to spend Easter with were the friends I attended that ceremony with. I practise with these ‘Vajra sisters’ every week on Zoom, so I ‘know’ them; but to be in physical presence brought both a knowing, and not knowing. I found myself both nervous and excited. It was a joyful day, and sad to say goodbye.

Part 2 segued into Part 3: time with my old sangha, the dharma family that came into being 11 years ago. We didn’t drive back to NYC for this reunion, but rather north to upstate NY. Many of my Brooklyn / Manhattan friends moved out of the city at the beginning of the pandemic. Most were ready to move anyhow – I got a sense of ‘why’ in those first few days of the trip: the polarity of all that the city offers, and all it denies. Age-ing? Sage-ing? The world has changed; we have changed. Everything changes. To move; to find ‘home’; to find a place that allows inner and outer to resonant, to be in accord.

We spent three days with these dear people. Three days of reminiscing, three days of exploring how our current being(s) maintained the intimacy of our first encounters a decade ago. To sit opposite one another at the dinner table; to sit opposite one another via Zoom. Grateful to be in physical presence; and appreciative of the online platform. It reminded me a little of discussions I have facilitated with therapy trainees since the pandemic and an era of online therapy. One mode is not better than the other, they are just different. Needless to say, I DO prefer being in person with friends, and yet there is an intimacy allowed – maybe even optimised – through the online medium.

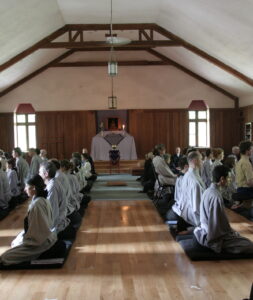

The second part of Part 2 beckoned: back to my ‘new’ sangha siblings, and attending a retreat at the Zen Mountain Monastery. I hadn’t practiced in the Zen tradition previously, and it wasn’t the intention behind signing up for the weekend. I found myself there after Judy Lief, a senior student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and the teacher under whom I now practise, advertised the programme that was to discuss the mahamudra teachings. Too auspicious to ignore: the retreat only 20 minutes from where I was staying with friends, with the teacher I took my Bodhisattva vow with, AND the topic being a system of teachings and practices I find myself deeply connected to. Flights changed, stay in the US extended.

All this to say – the whole trip to this point was conveying the ‘both / and’, and yet it remained implicit in experience. There was a felt sense of an oscillation between comfort and sensitivity: as if I was swaying between right and left feet. It was in the retreat that I was able make the implicit, explicit. The contrast set up by Zen container: the 4:30am rising for practice, the strict form and ritual of Zazen; with the ‘play’ and spaciousness of the mahamudra teachings presented in Judy’s mischievous style. Both stillness and movement.

Zazen, as we were instructed at ZMM, asks of the meditator to sit “like a mountain”. One sits in correct posture and counts the breath to a count of 10, repeating this over the course of the 40 minute sit. There is then a period of walking practice where attention is placed on the footfall rather than the breath. After 10 minutes, one returns to the Zafu and readies oneself for another 40 minutes of Zazen. As well as these 2 hour sessions of meditation, we attended “service” each day: a 30 minute ritual containing bows and chants. The stillness and form of Zen.

Zazen, as we were instructed at ZMM, asks of the meditator to sit “like a mountain”. One sits in correct posture and counts the breath to a count of 10, repeating this over the course of the 40 minute sit. There is then a period of walking practice where attention is placed on the footfall rather than the breath. After 10 minutes, one returns to the Zafu and readies oneself for another 40 minutes of Zazen. As well as these 2 hour sessions of meditation, we attended “service” each day: a 30 minute ritual containing bows and chants. The stillness and form of Zen.

Mahamudra, as I have come to know it through teachers such as Mingyur Rinpoche and his brother Tsoknyi Rinpoche, is a formless practice coming from the Tibetan lineages of Buddhism. Both Zen and Tibetan Buddhism emphasise the view of the mahayana; Tibetan Buddhism however adds another ‘vehicle’, the Vajrayana. It is here that the Mahamudra teachings come to life. As teacher Gaylon Ferguson explains:

Mahamudra, as I have come to know it through teachers such as Mingyur Rinpoche and his brother Tsoknyi Rinpoche, is a formless practice coming from the Tibetan lineages of Buddhism. Both Zen and Tibetan Buddhism emphasise the view of the mahayana; Tibetan Buddhism however adds another ‘vehicle’, the Vajrayana. It is here that the Mahamudra teachings come to life. As teacher Gaylon Ferguson explains:

“Formless meditation might appear more mysterious than it is. There’s a sense in which the attitude of formless meditation—which is not to manipulate whatever arises in our experience—is there whether we’re doing practice with form or without form. There’s a continuity between the two. Appreciating them both is a matter of understanding the view of the teachers of the lineage; namely, that one could practice without any gaining idea, without pushing anything away, but nakedly and directly experiencing the vividness of whatever arises in one’s experience, whether that’s emotional experience or perceptions of the world. Nowness is really the essence of formless practice as well as practice with form.”

No counting, no object for meditation. In mahamudra, the instruction is to simply abide without any judgment of what is arising in experience – thoughts, perceptions, emotions. The more we settle into the experience, there is a sense there is no observer nor observed; there is simply “abiding”. Abiding with the play; both the stillness of awareness and the movement of appearances.

I have studied and practiced mahamudra in the four years since entering the Vajrayana. And yet there was something about the contrast between the form and space of Zen, the play and energy of mahamudra that brought home the nonduality at the heart of all Buddhist lineages.

Why is this so impactful, why is this so important? The crux of the Buddhist view is that suffering stems from believing we are a separate self; we split the world into a series of dualisms: self and other, subject and object.

Old friends, new friends

Frenetic city, peaceful rural retreat

Muted colours of the Zendo, the vibrancy of Tibetan meditation halls

Stillness of the body, movement of the mind

Not the same, but not different; not as separate as we make them to be. Life as a dance of opposites, a play of polarities. One not existing without the other.

Practice on the meditation cushion allows us to recognise experience as not so differentiated; and with time we come to take this out into the world, into everyday life. Certainly for me, it was has allowed me to appreciate the ‘both / and’ quality of life, the polarities of experiences, as simply a display. To hold sadness / joy, difference / familiarity without preference, and no need to control.

…not all the time, this is a practice after all!

—————-

*This could sound like a Tibetan Buddhist teaching, lists with sublists!