Finding a little more freefall after a period of stuckness, I am engaging with my writing with much enjoyment. I am getting in a pattern of “Monday-for-Friday”: reflection and research on Mondays, bringing my ideas onto the page on Friday. Already I feel I am introducing the theme of this post – as the creative act has something to communicate as we consider existence and essence. I am getting ahead of myself…

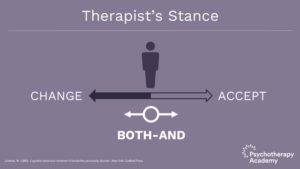

The main objective of this autumn (now I am seeing the irony of the Americans referring to this season as the Fall!) is to pen a series of blogs that will examine the key concepts of the humanistic therapeutic tradition as I pave the way to describing a humanistic psychotherapy in book number 2. The thesis I am developing for this book is the importance of riding the tension of opposites as we tread the healing path as a therapist and as a client. This play of opposites is what the ancient Greeks proposed in their practice of dialectic. Plato would present philosophical arguments back and forth in dia-logue (dia, Greek from through, across, from point to point) between two characters (often Socrates talking to his interlocutors). Hegel would develop this method in his thinking – and we humanistic practitioners (whether we realise it or not) benefit from using the dance of opposites as a fundamental touchstone*

What I am passionate about is bringing back a balance to humanistic practice. Many training courses understandably value the insights of existential-phenomenological philosophy: and I owe much to what these inter-related branches bring to understanding the human condition. What I want to “bring back” as such is the ‘other’ paren alongside; the power of humanistic psychology. I appreciate how the generalising of the “ology” can cast a shadow over the particulars of human existence; and yet for me the value-added that the founders of the human potential movement offer is so much more than a one-sided optimism and individualistic take on life. If we ignore one parent, the parent that is humanistic psychology, we would have to disregard the writings of Rollo May, James Bugental, Kirk Schneider…and also to be frank, Carl Rogers. My thesis is to use the both / and of psychology and philosophy rather than throw out the baby with the bath water – to omit some deep branches of our roots would make for a lop-sided family tree! I agree with Schneider and Krug (2011) that the “existential accents on human limitation with humanistic accents on human possibility” is a combination that “creates paradoxical unity of complimentary opposites” (pg. 6)**

And so, the structure of Part 1 of my new text will follow this dialectical dance – a presentation of a series of couplets that invite the residing in-between and integration of the both / and (rather than the either / or that we are often left trying to reconcile). This week, we start at the very beginning…at least in the eyes of Jean Paul-Sartre…

Existence and essence

The very beginning, in two senses. Firstly, as in the name, existentialism takes as its primary concern ‘existence’ of human beings; and secondly, from a metaphysical position essence – the counter to existence – is commonly seen as the precursor. Existence is that something IS; essence is WHAT it is. Since classical times, philosophy has searched for natural characteristics that are inherent, unchanging, and innate. The sciences operate on this essentialist philosophy, continuing in earnest to break down reality into ever more fundamental laws and components. Cooper (2003) remarks that when the positivism of natural sciences pervaded the understanding of human beings, the pursuit became the revealing of “the universal, abstract, and unchanging truths” (pg9) going on beneath the mask: behaviourism came to see essence as stimuli and response, and psychoanalysis as id and superego. Existentialism is a reaction to the application of these essentialist ideas. To reduce Helen to a set of essential components and describe me as any one of my characteristics would be to diminish the fullness of my humanity. A central tenet of existentialism is people create their own essence through their actions and choices rather than being born with a pre-existing essence. I am Helen by living first and discovering who I become out of what I have created for myself. With this existential approach “a whole new idea of selfhood emerges” (Van Deurzen and Arnold-Baker 2005, pg 160). ‘Self’ not as a substance or thing with some pre-given nature / essence but as a situated activity always in the process of making or creating who we are as our life unfolds (more on such thrownness later!).

This central tenet of existentialism was encapsulated by Sartre in the pithy adage “existence precedes essence” (1943, pg 568) but the principle originated with Heidegger in Being and time, “The ‘essence’ of Dasein lies in its existence” (1927/1962 pg.42). In other words through our existing (verb) we come to be what we are (noun). The aim of existential philosophy is thus to develop a more complete understanding of this existence; “the irreducible, indefinable totality that you, me, and others are” (Cooper 2003, pg 10); yet knowing there can be no complete or definitive account of being human because there is nothing that grounds or secures our existence. Fundamentally we are ‘unsettled and incomplete’. This is at the root of Kierkegaard’ somewhat confusing description of existence as “a relation that relates to itself” (1848, pg 13). Existence is a reflexive or relational tension between “facticity” and “transcendence”: we are constrained by our givenness but simultaneously endowed with the capacity to rise above the facts of our existence. “If man […] is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be” (Sartre, 1946 pg 293).

Having freedom to be ‘self-making’ isn’t necessarily always the case. I want to give the closing words to Simone de Beauvoir, as up until now the pronouns surely testify women are Le Deuxième Sexe (1949). Accepting Sartre’s existentialist precept that existence precedes essence, she insisted that one is not born a woman, but becomes one. She identified, as the fundamental basis for the oppression of women, the social construction of woman as the quintessential “Other.” Man, by contrast, is a “Self.” Beauvoir thought that the process of becoming a “Self” or “Subject” requires an element of “Other” as well as “Self,” and that, thus far, woman has been only “the incidental, the inessential, as opposed to the essential.” “He is the Subject, he is the Absolute—she is the Other; an object of man’s oppression. At the time of writing her treatise, Beauvoir sets out to explore the situation of women as enslaved and “immanent” with a view to challenging it. Whilst man might well transcend his facticity, she argues that woman cannot – as “like a passive victim” she is told what her nature is. I hope we are someway to enabling women out of this oppression.

—–

When I think of the ‘gang’ that Sartre and du Beauvoir were a-part-of, another name that comes to mind is that of Alberto Giacometti. I was awe-struck when I saw his work exhibited at the Tate Modern some years back; and when pondering “existence precedes essence” it is his statues that bring something of the entire existential cannon to life for me***. And I have been thinking of how art can help us understand Sartre’s initial basis for his argument – as he started with a consideration of an artist’s tool: the example of the paper cutters. Sartre likens the knife’s manufacturer to the traditional idea of God as creator.

When I think of the ‘gang’ that Sartre and du Beauvoir were a-part-of, another name that comes to mind is that of Alberto Giacometti. I was awe-struck when I saw his work exhibited at the Tate Modern some years back; and when pondering “existence precedes essence” it is his statues that bring something of the entire existential cannon to life for me***. And I have been thinking of how art can help us understand Sartre’s initial basis for his argument – as he started with a consideration of an artist’s tool: the example of the paper cutters. Sartre likens the knife’s manufacturer to the traditional idea of God as creator.

“When God creates he knows exactly what he is creating. The concept of man, in the mind of God, is comparable to the concept of the paper knife in the mind of the manufacturer: God produces man following certain techniques and a conception, just as the craftsman, following a definition and a technique, produces a paper knife. Thus each individual man is the realization of a certain concept within this divine intelligence.”

– Existentialism Is a Humanism

So what of the statues that Giacometti created? First there is an idea, then that idea becomes instantiated. In this view, an essence precedes the form coming into being. If we don’t subscribe to the idea of an divine creator, human beings certainly aren’t “an idea” that comes into being. And is art really that too? I know as I write, the form as it is taking shape informs and creates the message – it feels more iterative than formulaic. And so, when I think of Giacometti and his existential figures – I cannot imagine they formed solely from an idea; nor was their essence the clay / plaster / bronze: I imagine more so that as he shaped, their essence – the lived-experience they conveyed – was being written in their agitated textures and inferred movement.

Certainly, the works of sculptors such as Amber Arifeen are testament to this: I found her work when researching some of this ground. She shares “One might be quick to think that it is these curves that give the forms their “female bodily” essence – however the process with which these forms were created and transformed subverts this notion, demonstrating that it is the “existence of the forms that precedes the essence”.

As I have written previously, art can teach us much about phenomenology and indeed, the art of being human. I want to learn more about Giacometti as I think he can reveal much more about the lived-experience and illustrate this dance of dialectics.

————-

* Gestalt therapists like myself know it (arguably) more explicitly through notions of ‘polarities’.

** As a note, the posts over the coming weeks will cite references like this but I won’t include the full reference. If there is something you like the look of, please don’t hesitate to contact me and I will share more detail

*** In my research I came across a whole host of resources linking Giacometti and the existential movement – this is a good starting place