This is week three of our journey down the pinball alley of dialectics that, for me, make up the existential-phenomenological tradition of counselling and psychotherapy (also known as the humanistic tradition – since the philosophy aims to describe the experience of what it is to be human). As I explained a few weeks ago, it is a dialectic or zig zag path; a back and forth between two seemingly extreme polarities of experiencing. A resulting definition of well-being is our capacity to embrace the both / end of all the vicissitudes of existence: one might say a quality of awe that includes awe-ful and awe-some. This week, we move onto couplet three, the dance between…

Freedom and limits

We are thrown into existence and without a determined essence, this no-thing-ness provides a potential to create who we are. Human existence as being fundamentally free lies at the heart of the existential tradition. This differs to psychoanalytic and behavioural traditions that assert unconscious drives or behavioural reactions to external stimuli determine our acts (Cooper, 2003). While Kierkegaard was writing about freedom as far back in the 1800s, it is perhaps Sartre who is foremost of the existentialists writing on the matter: and we need to consider the context of occupied France in the 1940s as to why he would be stressing freedom not as an add on, but at the very essence of being itself. “Man does not exist first in order to be free subsequently; there is no difference between the being of a man and his being free (1943 pg 25). Take now for example: you and I are both expressing our freedom. On a day on which I am seeing no clients, nor am I teaching, I have the freedom to spend my day writing. Likewise, you have sufficient freedom to be reading this text. Cooper (2003) invites a similar reflection, taking the exploration more deeply into the lived experience: “As you read this for instance, you are unlikely to experience yourself as being impelled…to turn the page” (pg 14), and goes on to distinguish wanting to and being deterministically impelled to do one thing or another.

Yet this freedom is not doing whatever we want! Freedom, defined in the existential tradition, is the capacity for choice within natural and self-imposed limits of living (Schneider, 2008). We are “the incontestable author of an event or of an object” (Sartre, 1943 pg 553) and simultaneously ‘hedged in’ in innumerable ways (Cooper 2012). The natural limits of our life begin with our thrownness; being born into a world that is not our making (Heidegger 1927) and a trajectory hurtling towards a death we cannot avoid (Yalom, 1980). It’s not smooth sailing in between either: we constantly encounter the realities of living. Life is beset with ‘boundary situations’ (Jaspers, 1932), or ‘givens’ (we will come back to Yalom’s descriptions later). Similarly, May (1981) in his exploration of Freedom and Destiny describes how our vast potentialities are matched by crushing vulnerabilities. Cosmic destiny must embrace the limitations of nature; genetic destiny entails physical dispositions; cultural destiny encompasses social patterns; and circumstantial destiny folds in situational circumstances. As well as external limits that include earthquakes, life span, birthright or redundancy, we are also undoubtedly (yet often unwittingly) imposing limits on ourselves through culture, language and lifestyle. The aim of an existential-based therapy is to “set clients free”(Schneider and Krug, 2010) through an examination of our freedom. “The reality and ambiguity of our situated freedom is something with which we are both faced and blessed in every moment of our lives” (Craig 2012, pg 17).

Clients will come with idiosyncratic versions of how difficult it is to surf the “huge tide of accident” (Jaspers, 1932) that life can be. There can be problems of not seeing where there is freedom i.e. where self-imposed limits exist; and equally there can be a sense of too much freedom. As Cooper (2012) points out we inhabit a world of tensions – too many freedoms and choices that can often feel in conflict. Dilemmas of choice can lead to paralysis (or impasse), for instance our desire for independence and a need for closeness. So while the freedom to do or to act is probably the clearest form of freedom, as Schneider and Krug (2010) suggest, much of our work might be helping clients experience the freedom to be. May (1981) saw this as our most fundamental freedom, and if our attitude to a given situation is limited, it is this internal stance that binds. ‘Bound’ because we have not yet released the capacity to create meaning through imagining and inventing, processes that physically and psychologically enlarge our worlds (Yalom, 1980). The existential definition of a ‘real self’ is one that is ever-changing and free to do so in a creative process (Pollard, 2005) that throws off the shackles of introjects and scripts. Whilst Heidegger emphased the aspects of our human existence that we are not in control of i.e. the limitations on our freedom in the world in which we find ourselves embedded, he was also adamant in his emphasis that we can choose how to respond to our situation – what we embrace of culture for example. Phenomenological reflection reveals that such freedom is an integral part of human lived-experience; and one dimension of our client work is to assist clients in seeing this, and to thus resist the call to ‘bad faith’ (Pollard, 2005).

Clients will come with idiosyncratic versions of how difficult it is to surf the “huge tide of accident” (Jaspers, 1932) that life can be. There can be problems of not seeing where there is freedom i.e. where self-imposed limits exist; and equally there can be a sense of too much freedom. As Cooper (2012) points out we inhabit a world of tensions – too many freedoms and choices that can often feel in conflict. Dilemmas of choice can lead to paralysis (or impasse), for instance our desire for independence and a need for closeness. So while the freedom to do or to act is probably the clearest form of freedom, as Schneider and Krug (2010) suggest, much of our work might be helping clients experience the freedom to be. May (1981) saw this as our most fundamental freedom, and if our attitude to a given situation is limited, it is this internal stance that binds. ‘Bound’ because we have not yet released the capacity to create meaning through imagining and inventing, processes that physically and psychologically enlarge our worlds (Yalom, 1980). The existential definition of a ‘real self’ is one that is ever-changing and free to do so in a creative process (Pollard, 2005) that throws off the shackles of introjects and scripts. Whilst Heidegger emphased the aspects of our human existence that we are not in control of i.e. the limitations on our freedom in the world in which we find ourselves embedded, he was also adamant in his emphasis that we can choose how to respond to our situation – what we embrace of culture for example. Phenomenological reflection reveals that such freedom is an integral part of human lived-experience; and one dimension of our client work is to assist clients in seeing this, and to thus resist the call to ‘bad faith’ (Pollard, 2005).

Todros (2012) speaks of freedom in an even more ‘radical’ way: “a freedom that participates an ontological openness in which self, other and world cannot simply be objectified as ‘something that is settled’. In a beautiful and vivid description he juxtaposes the ‘madness’ of Narcissus and soberness of Heidegger. Both are concerned with freedom: The former acts for freedom FROM the wound, the latter encourages freedom FOR the wound. How so? In our therapeutic work, it is not simply to support a client in their exercising of freedom and agency in the face of life’s givens, and rather an invite to become more intimate with what appears, in actuality and possibility, with self and others and world. This radical approach is less Sartrean and more in line with Boss explains Todros; “Giving ourselves to the existential vulnerabilities of life constitutes a path of embodied intimacy” (2012, pg 75).

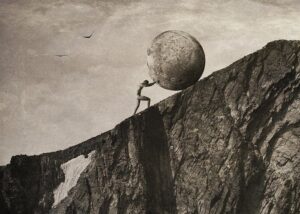

This brings to mind how much assistance and confidence I have taken in life from the myth of Sisyphus, the philosophical essay by Albert Camus (1942) in which he introduces his philosophy of the ‘absurd’. One might liken the absurd as lying in the juxtaposition and / or contradiction of our lived situation. And like our hero Sisyphus, we too are condemned to repeat forever the same meaningless task. Maybe its not pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll down again just as it nears the top, but with the call to surf the ‘huge tide of accident’ and then die (!) we have to engage the struggle. “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” (Camus, 1942, pg 55). This is the ‘tragic dimension’ of life that Nietzsche explored so deeply in The Birth of Tragedy (1910). And yet when we bring forth Todros’ invitation it is like Sisyphus engaging with the texture of the rock surface as he pushes; more engaged by the moment by moment aliveness of his senses; less focused on his plight ahead. “The gift of taking on the freedom that is ontologically given constitutes a greater creativity, to see the world and situations with a certain freshness and novelty; a freedom for a non-repetitive future, a freedom for possibility” (Todros, 2012, pg 75).

This brings to mind how much assistance and confidence I have taken in life from the myth of Sisyphus, the philosophical essay by Albert Camus (1942) in which he introduces his philosophy of the ‘absurd’. One might liken the absurd as lying in the juxtaposition and / or contradiction of our lived situation. And like our hero Sisyphus, we too are condemned to repeat forever the same meaningless task. Maybe its not pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll down again just as it nears the top, but with the call to surf the ‘huge tide of accident’ and then die (!) we have to engage the struggle. “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” (Camus, 1942, pg 55). This is the ‘tragic dimension’ of life that Nietzsche explored so deeply in The Birth of Tragedy (1910). And yet when we bring forth Todros’ invitation it is like Sisyphus engaging with the texture of the rock surface as he pushes; more engaged by the moment by moment aliveness of his senses; less focused on his plight ahead. “The gift of taking on the freedom that is ontologically given constitutes a greater creativity, to see the world and situations with a certain freshness and novelty; a freedom for a non-repetitive future, a freedom for possibility” (Todros, 2012, pg 75).

The couplet of freedom within limits (Schneider and Krug, 2011) brings to the fore a basis for personal ethics and values. The creative process that is the ‘real self’ is marked by both freedom and responsibility (Pollard, 2005). Sartre points out we are creators of our own values: “My freedom is the unique foundation of values…and nothing, absolutely nothing, justifies me adopting this or that particular value (1943 pg 38). The culmination of a more embodied openness, a “being at home in one’s body and world” leads to “empathy for others as fellow carriers of existential vulnerability” (Todros 2012 pg 75); an awareness that our existence as a being-in-the-world-with-others is to recognise that my freedom will impact on another’s freedom. For instance, while we might contest we are free even ‘to be a danger to ourselves’ (Szasz, 2004), to meet the absurdity of life with a decision to end it is a conversation with clients that therapists at any stage of their career will experience as testing. Camus claims that ending life is not justified and instead requires “revolt”. “To a man devoid of blinders, there is no finer sight than that of the intelligence at grips with a reality that transcends it’” (Camus, 1942 pg 26); and yet who are we to urge that in our clients? The counselling and psychotherapy profession claims to offer a space for free dialogue and yet it too endangers a “normalising tendency” (Pollard, 2005 pg 266). There is no doubting that the existential grounding offers a framework for such conversations; or “calls people to wake up and claim their freedom” (Pollard, 2005 pg 266) whether it be how to live their life or to rethink the ideologies that govern their existence.

To integrate freedom and limitation is to emancipate clients from their polarised conditions and instead to experience their possibilities (May, 1981). As we will come back to time and time again, it is only in the leaning into experiencing (not just dialoguing) of these freedoms, limits and the tension between that change processes will take place in the therapy room. “If life limiting patterns are experienced in the present, then clients will be more willing and able to choose life-affirming patterns in the future” (Schneider and Krug, 2011 pg 15).

I hope you have enjoyed this third of (what is currently planned as) fourteen couplets. Today my day of writing will take me halfway through these, and I look forward to sharing them with you between now and the end of the year. I will be taking a break next week, as I go on my annual (and solitary) retreat. So expect my next post to be sharing some news from my time away.