A few weeks ago I had a powerful experience that left me feeling compelled to engage more actively with a feminist view and life. I was attending an online meeting with someone I had not met before; and while it was an interesting meeting in which the dialogue highlighted similarities and common ground, over time, I started to feel more and more uncomfortable. In fact it was only afterwards that I was able to recognise the level of activation I had been experiencing. I had been wanting to leave, to escape, and yet I saw myself nodding, smiling, going along with. I had no idea how long the meeting was going to last, and yet I felt unable to clarify. You could say I was paralysed; I was certainly disempowered.

As I sat down to have dinner with my wife, I realised I was a little shaken and shocked. She mirrored back that “it sounds like mansplaining” – yes, the meeting was with a man, and the tone and manner I encountered DID feel patronising, condescending; and yet it was more nuanced than that*. What I was reeling from was a power differential. I felt talked at; there was no room for me and my experience in that ‘dialogue’.

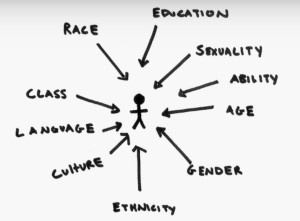

I shared my experience with trainees on our counselling courses in a lecture session the next morning. The session allowed staff to share how life experience had shaped our ‘cultural competence’. I disclosed how gender, sex, sexuality had not really been on my radar until fairly recently – even as a middle-aged, gay woman who has spent most of her adult life working in Higher Education, in science, in sport (a perfect trilogy of white, male dominated arenas!). These past pandemic years have felt like a pressure-cooker, one in which several social-cultural-economic ingredients have bubbled the collective pot. And while many have realised, recognised and are working through ‘colour-blindness’, I am also figuring out how I have been blind to issues of intersectionality.

I shared my experience with trainees on our counselling courses in a lecture session the next morning. The session allowed staff to share how life experience had shaped our ‘cultural competence’. I disclosed how gender, sex, sexuality had not really been on my radar until fairly recently – even as a middle-aged, gay woman who has spent most of her adult life working in Higher Education, in science, in sport (a perfect trilogy of white, male dominated arenas!). These past pandemic years have felt like a pressure-cooker, one in which several social-cultural-economic ingredients have bubbled the collective pot. And while many have realised, recognised and are working through ‘colour-blindness’, I am also figuring out how I have been blind to issues of intersectionality.

Let me throw something else into the bubbling, alchemical pot: having been a female in a male dominated environment, I must recognise how I have the potential to “mansplain” – I imagine I have done that a fair bit along the way: women very often need to take on more masculine characteristics in order to fit in, to climb career ladders, to get recognised. I have written about the masculine and feminine principles previously on my blog, particularly the work of Jungian psychologist Gareth Hill. My therapeutic journey has also helped me identify the complex relationship I have with authority – how I project it on others and only step into my own power in a clunky way**. Clunky can sometimes equal ‘teachy’ when I am in relational dialogue.

My teaching role therefore gives me many opportunities to work with this energy. Firstly, how I relate to the students and ensure I maintain enough space for them to share their own experiences (and not be the fountain of “truth”, whose truth is that anyway?). It is a perfect paralleling of what I am inviting them to develop: the awareness that we ALL possess masculine and feminine energies. Secondly, how the most healing psychotherapy is one that comes from a more archetypal divine feminine. This past week I had a wonderful moment with one of my final year students: halfway through a group tutorial, she gasped, sat back in her chair. “Oh wow, this all feels so much like the female energy in parenting”. This “a-ha” had dawned as we talked about receiving our clients; receiving them on an embodied level, not an intellectual, heady, theoretical one. This is why I treasure the Humanistic approach to psychotherapy. While Carl Jung is often attributed with theorising the masculine and feminine, for me ‘best’ practice is inherent in the Humanistic tradition because it emphasises wholeness. I guess it can sometimes get lost in the language of ‘growth’ because that takes on a societal ‘betterment’ (which activates our masculine drive, diminishing our feminine spaciousness and ease).

What does a psychotherapy grounded in the feminine principle look like? There are several sources that can help this pursuit; and Carl Jung’s work is definitely one source we can tap into. Barbara Stevens Sullivan’s excellent text opens with the thesis:

“that therapeutic work of all theoretical persuasions has been significantly impaired by the dominant cultural imbalance between the masculine and feminine principles. Good therapists…must do much of their best work in opposition to a severe cultural bias that denigrates nurturing, receptive, accommodating behaviour and idealises active, assertive, controlling behaviour”.

Therapists can self-monitor – to watch their doing, and bring forth more being; to avoid directivity and expertise, and bring out more of the client’s wisdom with receptive, embodied, deep listening and presence. This is not about eliminating the masculine: as I have written about recently, this is about balancing the top down and the bottom up in our psychotherapist armoury.

This view reminds me of the field of ‘care ethics‘; itself a feminist philosophical perspective that uses a relational and contextual approach toward morality and decision making. Whilst Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach made huge steps to countering an under-theorising of ‘care’ in psychotherapy, we still unfortunately live in the shadow of early days when it was a new field trying to establish itself within the medical model of technique and positivism.

This view reminds me of the field of ‘care ethics‘; itself a feminist philosophical perspective that uses a relational and contextual approach toward morality and decision making. Whilst Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach made huge steps to countering an under-theorising of ‘care’ in psychotherapy, we still unfortunately live in the shadow of early days when it was a new field trying to establish itself within the medical model of technique and positivism.

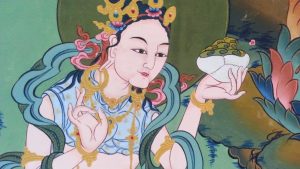

I love the synchronicity of life; as just this week I had the opportunity to attend a webinar with Buddhist teacher and author Anne Klein, one in which she spoke about the Tibetan Buddhist master and teacher Yeshe Tsogyal. Considered the highest female practitioner in Tibetan Buddhist history, Tsogyal was born in the year 777 and has become a central practice figure in expressing the divine feminine. I found myself incredibly inspired by Anne Klein’s talk, touched by the capacity that Yeshe Tsogyal embodies – a wholeness of being that goes beyond binaries; difficult terrain for many to navigate in these times. Klein stressed Yeshe Tsogyal’s energy as being un-binary rather than non-binary. That in fact, the divine feminine and divine masculine have never been separate. The talk helped me understand more deeply that while there is difference, to confuse this as separate is where we, as individuals and as collective society run into problems. So strong has the masculine become, it has separated itself, dominated itself. In fact, this is so pervading that it has forgot its strength comes from its partnership; and having lost its balance it has lost its wisdom.

I love the synchronicity of life; as just this week I had the opportunity to attend a webinar with Buddhist teacher and author Anne Klein, one in which she spoke about the Tibetan Buddhist master and teacher Yeshe Tsogyal. Considered the highest female practitioner in Tibetan Buddhist history, Tsogyal was born in the year 777 and has become a central practice figure in expressing the divine feminine. I found myself incredibly inspired by Anne Klein’s talk, touched by the capacity that Yeshe Tsogyal embodies – a wholeness of being that goes beyond binaries; difficult terrain for many to navigate in these times. Klein stressed Yeshe Tsogyal’s energy as being un-binary rather than non-binary. That in fact, the divine feminine and divine masculine have never been separate. The talk helped me understand more deeply that while there is difference, to confuse this as separate is where we, as individuals and as collective society run into problems. So strong has the masculine become, it has separated itself, dominated itself. In fact, this is so pervading that it has forgot its strength comes from its partnership; and having lost its balance it has lost its wisdom.

As a psychotherapist, this loss of wisdom happens when we become too heady, too theoretical; when we lose our embodied, direct experiencing. Rene Descartes, with his dictum “I think, therefore I am” set up a split between mind and body; one that we as individuals and as collective society, have struggled to repair since. If we can split our own experience, we see the world in separation; of subject and object, of me and not-me, of self and other. And once there is separation, comparison soon follows. Women have been living with that comparison, for years, consciously or unconsciously: in families, in relationships, in work. And just to express this now risks judgement – as Sara Ahmed in her brilliant book “Living a Feminist Life”, just speaking to this disparity makes me a feminist killjoy. By pointing to a problem, I become the problem. I am just relieved that I know see the problem having been blind to imbalance for the majority of my life.

I am now ready to live a more feminist life; to take up female role models, adopt archetypes of the feminine, to see our wisdom, to feel our strength. I do this for me, I do this for my female ancestors, and for the females in the lineage to come. This is not an anti man, anti male agenda – this is counter to any bifurcation. This is about honouring equality, and to be willing to stand my ground.

Wishing all my sisters a brilliant International Women’s Day!

——–

*We must take care with language. I value that such phenomenon are being called out, and labels help something become known and more visible. But generic terms endanger the specific. It is why as therapists we always check in with clients what they mean when they use words, metaphors, cliche to describe experiences – what is actually meant?

**I might touch upon this in next week’s blog, when I plan to share some of the teachings of the Enneagram. I resonate with the characteristics of the enneatype “Six”, doubting my own authority and giving it to others so that they might offer me protection from uncertainty.