Last week I completed a first draft of my book; one week ahead of the deadline I had set for my trip to France – part practice retreat, part book immersion. I will spend my mornings in practice with the yidam Vajrayogini, and my afternoons – keeping her in mind – sat at my desk overlooking the Normandy countryside. The intention is not to start the substantive edit but more to come back from France with an idea of what is left to do: a cover to cover read checking out does it flow, does each section convey the main thrust of my proposal for what is a humanistic psychotherapy? Only then will I broach the proposal with my publisher. It starts to bring a 3 year process toward completion. Busy and exciting times ahead in the coming months!

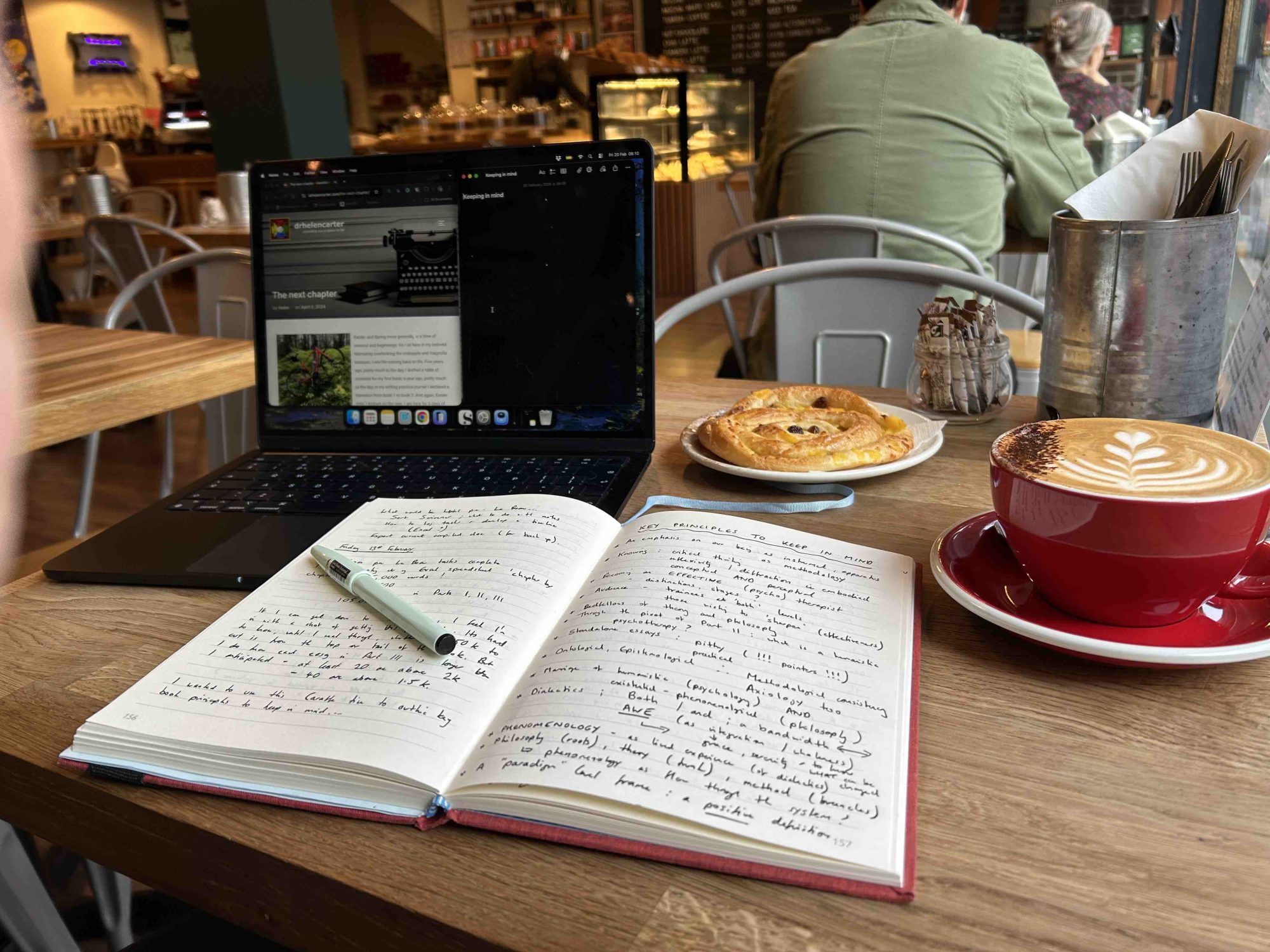

And so, here I sit in my happy place at a certain cafe in my home town of Lewes. Last week I sat in this same place, sketching out in my writing notebook what are the main themes and principles of the text. As someone who marks a lot of assignments and sees varying degrees of someone sticking to task, I am mindful to keep in mind the central tenets set out in the preliminary chapters and not losing the main threads in what I am weaving: and that is really easy to do over the course of three parts and over 200,000 words! Writing this blog is another way to help solidify and keep in mind the main theses.

Having reached this ledge in the ascent, I have shared the achievement with various people: friends, colleagues, trainees, supervisees. One of the most rewarding experiences in these moments has been on revealing the title, how it has been greeted with a confirmatory “ah, yes” Given the target audience of this text, this indication that I’m hitting a resonant note is incredibly motivating.

Humanistic psychotherapy: experiencing second-order change

Let me break that title down.

- Essentially the book is my attempt to present a humanistic model of psychotherapy, defined in the positive rather than saying what it isn’t, or in reaction to (i.e. psychoanalysis); furthermore, to give the readership a clearer articulation of what it is at the level of the paradigm (not at the level of the modalities that tend to sit under the umbrella term).

- The second part of the title firstly brings us the centralising of experience: an emphasis on the therapist’s being as the instrument of the work*, and this comes to help the client know their own subjectivity (importantly, how to come to know it).

- And, second order change loops us back to the psychotherapy in the title. The humanistic tradition comes from a history and culture of counselling; as the book will unpack, how do we approach such terms, and how might we differentiate what is arguably a holding counselling and a deconstructing psychotherapy: a deconstructing brings a change to the system rather than a re-stabilising of it. This is a brief synopsis: it is far more complicated argument.

In the early chapters, I set out my position: that in my experience and understanding, an effective humanistic psychotherapy relies on the practice of phenomenology. I am amplifying phenomenology not to deny the importance of the existential bedfellow, but rather to help trainees and others wishing to sharpen their therapeutic blade, thus balancing the conceptual and the perceptual. Experiencing, or knowing rely on both sources. Ideas from existential philosophy are incredibly important; AND we need to help a client come to know how these aspects are lived. I’m also emphasising the dialectics of our experiencing human being. The notion of awe is a good example – how does this life contain awe-ful, awe-some.

Living is the back and forth “dance of the dialectic”; and, we might think of this as the therapeutic aim of the humanistic tradition, our capacity to oscillate and not fall into extremes.

As an educator of counsellors and psychotherapists, I am keen to bring over some of the bases of why it is important for the therapist to examine their knowing. I am often struck with the keenness to keep studying in this profession, which is excellent. However, do we keep in mind the through line of ontology, epistemology and onto methodology in our continued professional development? This comes up a lot in notions of being an integrative therapist and being clear this is not the same as a humanistic therapist. I won’t go into details here – but I do in the book. All this to say, I spend some time in the preliminary chapters talking about our history (and the importance of knowing our roots in both humanistic psychology and continental philosophy) and ensuring we maintain consistency in our view of the world, what sources of knowledge we look to, and how this becomes a way of practicing (i.e. those aforementioned “ologies”; to which I also add the importance of axiology). I give the image that we our roots in philosophy, a trunk of under acknowledged theory, and ultimately come to branch into the various modalities (person centred, gestalt, transactional analysis to name the big three). A common mistake is to learn the roots and jump to the branches, preventing us from tapping into the rich theory base that might help us understand a broader definition of humanistic psychotherapy. To take the metaphor and image to its limits, phenomenology might be like the flow through the roots, trunk and branches…

Phenomenology is, in my experience, the essential component of effective, psychotherapeutic practice through the humanistic lens. To not just practice the phenomenological method, but to theorise through a phenomenological lens too.

I didn’t come to this notion on my own; and I am not the first (for sure) to advocate for phenomenology in therapeutic and healing work. Again, I am an advocate for what is often missed, dare I say, not trusted as both necessary and sufficient. We don’t need to integrate other theories; although studying them really benefits our practice through critical thinking and reflection. This was the conversation I was having with the humanistic trainees on our psychotherapy Masters programme last week that brought in the topics and title of my text. I learned much of my capacity for critical thinking through my histories as a researcher: and speaking of which, a research study forms the pivot of this book.

Part 1 is mainly historical and contextual; Part 2 is an original research study I conducted two years ago – when I was first seeding the ideas for this to become a textbook. It was my intention to submit this research study to a journal; but the more I thought about it, I like it taking up its home as the segue that takes us Toward a psychotherapy. For the study, I interviewed counsellors who had gone onto train as psychotherapists, asking them what was that journey like and what (if anything) distinguished the stages and qualification? My conversation with these therapists allowed me to add to and deepen some of the features of an effective psychotherapy I had been considering in my work as someone who trains professionals at both PGDip (counselling) and MSc (psychotherapy) stages of their career. My teaching, my practice, my writing all feed into one another – I am really grateful for that.

After this pivot, Part 3 spends time going into some of the teaching points I tend to come back to every teaching year. Originally planned as a series of “pithy” essays that deliver practical guidance (from my own experience in the chair, in the classroom) to help people in the mastery of this healing craft, the now 60 draft essays are going to be the area of my editing – they are in themselves, enough for a book**. In each of these essays, I try to address the theme with the above mentioned foci and emphasis at the forefront of my mind:

- The dialectic tension at the heart of being human

- Using phenomenology to explore (and understand) the lived experience of the dance between polarities

- How this is the opportunity phenomenological working affords: to bring clients into an experiencing of what is being known…

- And health being the grace to know what can and cannot be changed

- I also want to argue that it is a phenomenological method that opens up possibilities; one that helps therapists (and therefore clients) understand how the past and future exists and plays out in our present

That present moment, relational immediacy is enough.

As I come to the end of this sharing, and bring my week ahead to the fore, I am excited and daunted in equal measure. I am sure I will experience many more oscillations across the two; and it will be interesting to have the “test tube” of my meditation practice to witness the ride. Undoubtedly, part of the excitement is the adventure of going back to my beloved Normandy. It’s a place that is special for so many reasons; a place that has contained and witnessed so many pivotal moments in my life, my practice, my writing efforts.

A home from home; and a place from which I am happy to launch this second book from.

———————

*I am reminded of Karen Barad’s assertion of apparatus being part of the phenomenon

**Thus a decision to be made – is this one or two books I am writing? Time in Normandy will tell!