I got married last week. How odd to write that? I say that because in many ways, my life and my self is no different to this time last week when I was not married. But when I stand back and say to myself “I am married” there is some disbelief. It is something about achieving a milestone, or as one of my friends said to me on the day itself, “as if you have become an adult”. And I imagine a lot of this internalised sense of “gosh” is taking part in a ritual, a ceremony, acknowledging a rite of passage.

I got married last week. How odd to write that? I say that because in many ways, my life and my self is no different to this time last week when I was not married. But when I stand back and say to myself “I am married” there is some disbelief. It is something about achieving a milestone, or as one of my friends said to me on the day itself, “as if you have become an adult”. And I imagine a lot of this internalised sense of “gosh” is taking part in a ritual, a ceremony, acknowledging a rite of passage.

My partner and I have been together for over a decade and for some time we considered why get married given we were committed to our relationship anyway. Yet it felt somehow important to have a public witnessing of our commitment to one another: to bring our friends and family together and celebrate love, life and the power of living a conscious relationship. Relationship to one another, relationship to our friends and family, relationship to our community. Relationship was what we were celebrating, honouring and committing to.

When I took vows to become a Buddhist 3 years ago, I was taking refuge in the three jewels – the Buddha as a role model of awakenment, the Dharma (the teaching of the Buddha) that points to the true nature of life and all phenomena, and to the sangha. The essence of sangha is not just that it provides community, like-mindedness and company on the Buddhist path (although those are aspects I deeply appreciate); sangha goes deeper, it is said to be a practice in and of itself. Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese monk and teacher, says “The practice of Buddhism should help people go back to their families. It should help people re-enter society in order to rediscover and accept the good things that are there in their culture and to rebuild those that are not”. And this was very much the spirit of our wedding day. A literal bringing together of our families: our family of origin and our family created of friends. And people witnessed our relationship and the intentions of our relationship in order to help us reflect those back to us in the coming weeks, months…and hopefully (!) years. The 55 people present will act as a community of mirrors: supporting, encouraging and guiding my partner and I in the coming years.

I think every single member of the community present understood that as well as the romantic aspects of the day (and it was truly a beautiful and sentimental occasion) there is a very realistic view too. In fact, our wedding “vows” were written (and shared) in the spirit of realism – and our friends and family came up to us throughout the day expressing how moved they were by our vows. We had spent considerable time reflecting upon what we would like to commit to in our relationship moving forward. Our experience so far had been how we had learnt from one another; how much we have changed through our relationship: and we wanted the formal marriage process to somehow honour this. And again, this is not all a romantic ideal. One conversation we had together was if we were to set up our married life as a container for individual growth, might that growth not only bring us together but also risk taking us apart? It is a beautiful notion “if you love someone, set them free”, but when you commit to that being a possibility, risk and fear can come up. We went to those places as we planned our vows.

And what IS a vow? As well as the legal declarations and contracting words of marriage in the UK, my partner and I wanted to write more personal vows or promises. Look in a dictionary and you will see how a vow is a solemn promise. Neither ‘vow’ nor ‘promise’ spoke to how we were framing our marriage intentions. Again the Buddhist frame came in to play: the difference between the commandments of Christian faith and the Buddhist precepts. The latter being less about rules and more about intentions to regulate behaviour or thought. We were expressing our intentions to try our best; and when we fall short, to try again…and again.

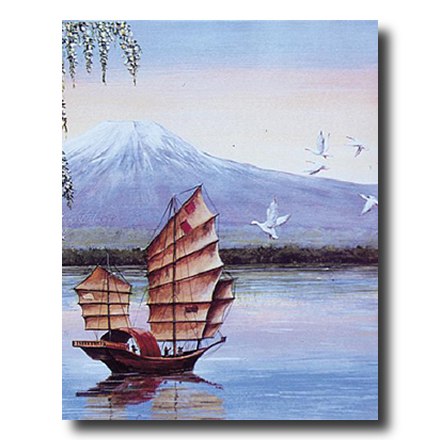

We came to a formulation of our relationship being a safe container in which we could grow as individuals and as partners. To use our companionship as a practice ground. And to this end, we decided to use the Buddhist teaching of the paramitas. The six ‘paramitas’ denote a process: “arriving at the other side”. We wanted to set up our marriage based upon these actions, to help us move beyond small motivations toward a relationship with a ‘sacred’ outlook. We each considered how we could bring generosity, discipline, patience, exertion, meditation and wisdom to our relationship; all said to be the enlightened activities of the bodhisattva or spiritual warrior. Essentially, we wanted to commit to each other’s “waking up”; to help each other see, trust and realise our basic sanity, our basic goodness. Taken together, the paramitas are often likened to a boat that takes us across the sea of suffering; and the bodhisattva is likened to the ferry operator whose sole purpose is to take passengers across the water. Or, like this description from Red Pine:

The paramita of generosity is the wood, light enough to float but not so light that it floats away. Thus bodhisattvas practice giving and renunciation but not so much that they have nothing left with which to work.

The paramita of generosity is the wood, light enough to float but not so light that it floats away. Thus bodhisattvas practice giving and renunciation but not so much that they have nothing left with which to work.

The paramita of discipline is the keel, deep enough to hold the boat upright but not so deep that is drags the shoals or holds it back. Thus bodhisattvas observe precepts but not so many that they have no freedom of choice.

The paramita of patience is the hull, wide enough to hold a deck but not so wide that it can’t cut through waves. Thus bodhisattvas don’t confront what opposes them but find the place of least resistance.

The paramita of exertion is the mast, high enough to hold a sail but not so high that it tips the boat over. Thus bodhisattvas work hard but not so hard that they don’t stop for tea.

The paramita of meditation is the sail, flat enough to catch the wind of karma but not so flat that it holds no breeze or rips apart in a gale. Thus bodhisattvas still the mind but not so much that it withers and dies.

And the paramita of wisdom is the helm, ingenious enough to give the boat direction, but not so ingenious that is leads in circles. Thus bodhisattvas who practice the paramitas embark on the greatest of all voyages to the far shore of liberation”

When I sat down to write my blog post this morning, I was thinking over the main theme I wanted to convey through the description of the wedding day and the idea of marriage as a container for growth and ‘waking up’. The essemtail theme is relating, as a verb; the relating process as healing, the relating process as a mirror to help us understand our blind spots. How that is happening on multiple levels: within the relationship between my partner and I; and how we are held in the community of our friends and family. I have also been considering my wish for this possibility for all beings to have this opportunity. To have relationships in which not only good times can be shared, but also challenging times can be endured and worked through for the ultimate growth and healing of individuals. Of course as a therapist I try to offer this to my clients; I also wish for my clients that they can transfer their relational experience and learnings from the therapy room in to everyday life; I also wish that through these learnings, harmful patterns can be illuminated and less likely repeated.

And for me, that was one of the most beautiful aspects of our wedding day. The way our community of friends and family were touched not only by the celebration, but also the intentions of our relationship. I hope they came to understand that they were the foundation from which we had the confidence to present our relationship as a learning ground. Their love and support is vital in this marriage. We also need our friends and family to celebrate life…and we certainly did that on the day!