Study of the lojong slogans at a time when my Buddhist community is in a state of instability has me working with a interesting conundrum. On the one hand, these ‘post-it note’ type proverbs remind me of our basic nature, which according to the Buddhist view is one of an inherent goodness; the Shambhala lineage is rooted in these teachings yet it is alleged that the current leader has not demonstrated this inherent goodness. How can we understand this paradox, this contradiction? Perhaps psychotherapy can offer us an explanation – and so in skipping to the punchline of this two-part blogpost: perhaps an overt focus on goodness misses the need to address our shadow.

Study of the lojong slogans at a time when my Buddhist community is in a state of instability has me working with a interesting conundrum. On the one hand, these ‘post-it note’ type proverbs remind me of our basic nature, which according to the Buddhist view is one of an inherent goodness; the Shambhala lineage is rooted in these teachings yet it is alleged that the current leader has not demonstrated this inherent goodness. How can we understand this paradox, this contradiction? Perhaps psychotherapy can offer us an explanation – and so in skipping to the punchline of this two-part blogpost: perhaps an overt focus on goodness misses the need to address our shadow.

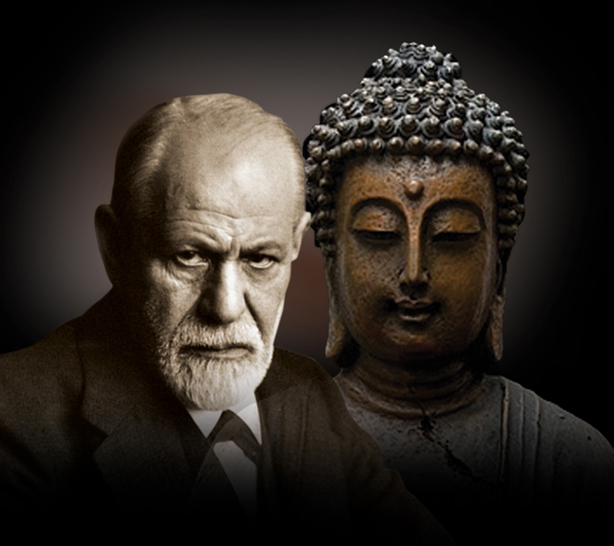

I wanted to start this week by preparing the ground for my thoughts: so a little theoretical background on how Buddhist and Western psychotherapeutic approaches view human nature. If we consider three basic ‘camps’ of thought: psychoanalytic (after Freud), humanistic (after Rogers) and Buddhist (after Buddha!) we might place them along a psychological health continuum.

At one end we have the psychoanalytic view, and a therapy that has much in common with the medical model and work of remedial in nature. Critics of psychoanalysis have often pointed to the approach’s “tragic world-view”, suggesting it to be a psychology of illness that neglects the health, creativity, intimacy and spirituality at the core of what it is to be human. Psychoanalytic theory rests upon the developmental view, one that takes the experience in the formative years to serve a profound impact well in to adulthood. It holds that by the age of 4 to 6, a capacity for repression of particular feelings is reached. We might call this “neurosis”: and as we probably all experience in day-today life, there is a ‘price tag’ to this achievement. The strategies that have long served the individual, and the associated parts of ‘self’ get pushed out of consciousness. These can act like a heavy anchor in life. In the opinion of psychoanalysis, ego function forms the inner core of a human being. If a person’s ego functions are almost completely impaired this would lead to a condition of psychosis; if they are less damaged but still extremely unstable personality disorders would follow; if the functioning of the ego is deemed adequate and personality structures are stable, a person might be considered having a neurosis.

Like psychoanalysis, the humanistic approach is founded upon a developmental model. Yet it offers a more optimistic, growth orientated view where humans have a potential ‘to maintain and enhance’. Carl Rogers, often attributed as fore-father of the humanistic therapeutic movement, considered people to be motivated by a need for enhancement and continuing development. In direct contrast to psychoanalysis, the humanistic tradition proposes human development governed by actualisation of a potential rather than motivated by ‘deficiency’. An individual only develops distress if inadequate conditions are present during interaction with others as we grow from infanthood to childhood i.e. actualisation is impeded. As a ‘being-in-the-world’ reliant on others for care and survival, a person may receive only conditional love or praise, an ‘ideal-self’. In the terminology of Gestalt, an individual comes to live under the rule of an internalised master or “Top Dog”. They are unable to fully contact their immediate experience choosing behaviour that is scripted to get what they need to survive (‘fixed gestalts’) rather than behaviour appropriate to the setting in the moment and according to their needs. The Humanistic traditions prioritise the intelligence and innovation of the individual with fixed patterns of behaviour seen as measures that prioritise survival over psychological flourishing. I imagine we can all call to mind ways in which we “shape-shift” to what we think others want of us rather than seeing to our own needs.

In contrast to the structural model of personality presented in Western psychology, the Buddhist model is one where the disturbances in ego function are located in external layers around a core of “Basic Goodness”, a fundamental nature of intelligence. The Buddhist view holds firm that every human is basically whole, healthy and good, but at some point in our development, due to certain causes and conditions, we lose access to this wholeness. The Buddha saw the distress (or dukkha in Sanskrit) that blocks us from our wholeness as being a part of the human condition. Dukkha, can be a subjective disturbance as mild as a momentary frustration (e.g. inability to park the car in a tight space) or as severe as a depressive or psychotic state. Like Freud, the Buddha located the source of human suffering in unrestrained impulses. One client of mine recently expressed how caught she gets with cycles of desire (for what she is “not allowed” to drink) and aggression (towards herself if she drinks what she is allowed and feels the impact of guilt and resolve to “never do that again”). She spoke to a painful, repeated cycle of anguish and disappointment. Unlike Freud, the Buddha was able to locate and address the original impulse of self-involvement, and how we create mental anguish through our perseverations, distortions, fantasies and internal commentary. My client and I discussed how the rule “this drink is bad for me” set her up for the suffering she was experiencing. What if she could sit with the feeling before drinking, whether she finally take the drink or not being less important? Much is rooted in our desire for things to go our way and the humiliation and despair when they are not.

I won’t get in to the depths of how each of therapeutic approach deals with psychological distress – not this week anyway. However, its worthhighlighting that Freud’s psychoanalysis considered there a necessary trade-off between impulse indulgence for social acceptance that resigned individuals to the inevitability of “ordinary human misery” even after a successful analysis. The humanistic tradition is again more optimistic, believing that with an exposure to compassionate relationship conditions the client can feel ‘met’ and accepted. Having this experience relationally goes a long way toward easing distress.

A Buddhism-informed therapy, such as one I bring to my client work, rests upon a fundamental view of Buddha-nature that shifts clients towards rediscovering a connection to something that was always there but simply obscured. In contrast to the developmental or Western view, this is a fruitional view. What does that mean exactly? If we go back to the client I describe above – she believes (like Adam, before taking the apple) that if she drinks the forbidden drink it proves she is “bad” (like the message she got from her father as a child). Many of us are caught up in the fantasy that is “original sin”, and we spend much of our time trying not to be the sinners we think we are and that preoccupies us as temptation. What if this client believed she is fundamentally good, and starts to see that the story “I am bad” is not core, but learnt? One way to do this is to help a client construct a history of their sanity, often done not through words or narrative but through an embodied awareness without interpretation and minimal explanation. So, rather than Western psychology’s search to find the reenactment beneath the current problems, Buddhist healing starts with seeing the neurosis as arising not out of pathology, but instead out of clarity and vulnerability.

How does this all relate to the question of basic goodness or basic shadow, and more specifically what we see emerging in many Buddhist communities right now? I will expand on this next week, but essentially I see it as relating to “Basic Goodness” being understood as a concept but not taken to an experiential level. People therefore “play” at it, act it…but without accepting the presence of, and working through the shadow, the pressure of holding it at bay often causes quite ‘explosive’ releases of historical (and karmic) material and patterns.

More next week!